Angel investing is not for the faint hearted. In my previous post in this series, I discussed the onset of the angel investing journey. In this, second, post I’ll take a look at ‘what happened next?’ across a series of my angel experiences. Truly, this is the Hindsight post.

Instant Riches?

What you’re hoping for, simply put, as an angel investor in a seed business, is that you’ve just backed the next Google/Facebook/Amazon/take your pick. You’re hoping your investment goes on to become a ‘Unicorn’, i.e. valued at above $1bn.

In the world of venture capital the professionals are generally looking for ’10x’ – i.e. making 10x their money – which often implies the business ends up, after taking on further rounds of investment, becoming a Unicorn.

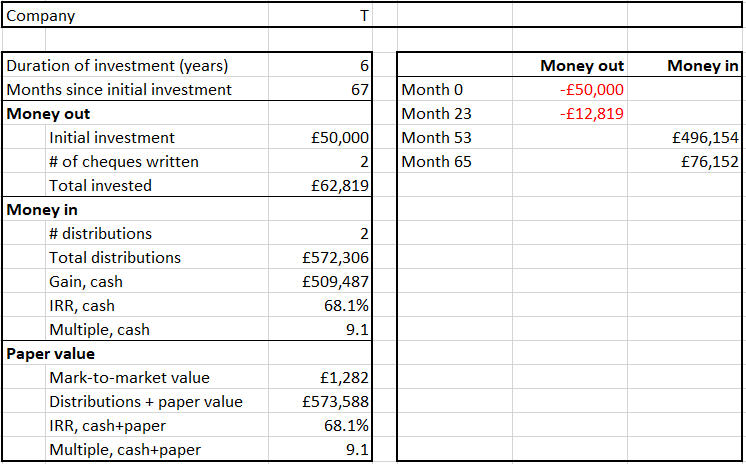

One of my best ’10x’ investments is company T, shown below. OK, so it didn’t quite make me 10x (though see below). But it exited quickly – the key money back came in month 53, with a small (15%) amount retained for a further 12 months.

You’ll notice that I added to my initial investment in month 23. Whether to ‘top up’/’follow on’ your investments is one of the hardest decisions you have to take in investing, in my experience. In the case of company T, I’m glad I did – even though by so doing my multiple fell (i.e. my month 23 investment was at a higher price than my month 0 investment).

Company T was one of the best angel investments I know. But nonetheless, one of its investors was really p*ssed off when it exited. Why?

Or a tragically early exit?

To get a glimpse of what might have been, consider company A – which was one of the best venture investments of all time. Company A made its investors 67x their money, in year 9. This worked out as 74% ‘internal rate of return’ – compound growth, in other words – for each year. It is this sort of return that is so alluring about investing in early stage technology businesses.

While company A was astonishingly successful, its IRR (annual return) was only a tad higher than company T’s. Company T exited after around 5 years. If it had maintained that annual return for another 3-4 years it too would have delivered a 60x multiple. It is this missed potential that frustrates the aforementioned company T investor.

Ultimately, a Unicorn

In reality, your ‘average unicorn’ takes a lot longer than five years to reach a billion dollars of value. Take company V, shown below. I invested early in this business, not once but twice in its first year. Then with a small top up a few years later. The business has gone on to become a unicorn business. But it has taken over a decade. 11-12 years later, I have taken out around 9x my initial investment. My remaining stake is worth, apparently, a further 20x my initial stake. It may take another few years before I can sell it.

I invested in Company V when its initial valuation was around $20m. Since then it has become a unicorn, worth more than $2bn – over 100x more. Yet my initial investment has ‘only’ multiplied by 10-30x. What’s happened here?

The answer is dilution – because it has raised a lot more money on the way up, and I didn’t always participate in those further investment rounds. This is a very common situation with fast-growth tech businesses. The lesson? Don’t immediately assume that your mate who was one of the first investors in Deliveroo/Monzo/Revolut/Farfetch has done quite as well as the valuation would suggest.

There is another point to make here. Yes, I invested in the early days of a Unicorn. But that was over 10 years ago. The IRR here is between 20-30%. That is good, very good, but not off the charts – especially considering the lack of liquidity I’ve had along the way. Amazon’s share price, when I invested in company V, was around $40/share. It’s gone up 50x since – a better return even than my unicorn investment.

The fast flop

Early stage angel investing is notorious for companies going belly-up. Sometimes, that happens almost instantaneously after launch.

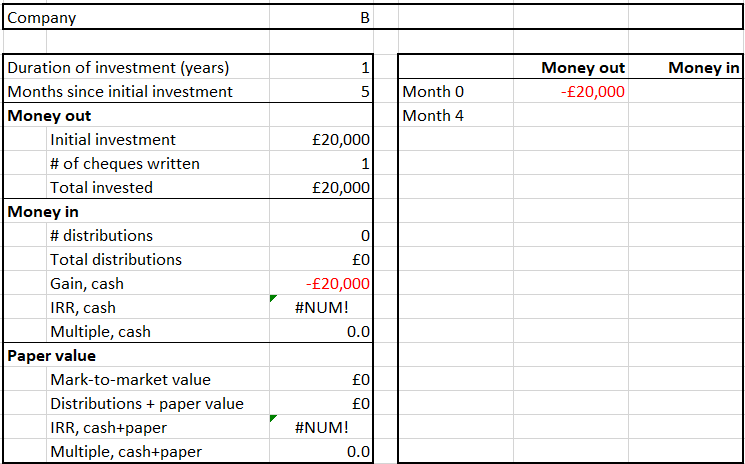

Take company B, for instance. One of my most ignominious and embarrassing investments. I invested for all the wrong reasons. Less than 6 months later, the business folded. That isn’t even my fastest flop, sadly.

And while I’ve highlighted the Fast Flop, the much more common variety is the Slow Flop. Usually a seed investment will be part of an investment round designed to last 12-18 months. It will usually take at least a year to know that your money has gone to a very dark place.

The hungry zombie

The next example is an important one. This scenario illustrates a very common dynamic in angel investing.

As I mentioned above, the hardest decision to make as an angel investor is whether to ‘follow on’. In company T’s case, I have followed my original investment no fewer than four times, over 6 years. My subsequent investments have been smaller than the initial one, but nonetheless I have now invested more than 2x my initial investment. There is no hope of any immediate money back, and I estimate my holding is ‘worth’ less than my initial investment.

Company T is basically a cash sink. But it still exists, and in fact has probably reached a point where it won’t or barely will need further funds. But it isn’t worth much either. A likely outcome is that it gets bought for paper/shares, and the acquirer then goes bust. But this is 1-2 years into the future.

Why did I invest in months 22, 24, 47? Was I expecting this time to make a big return? Was I an idiot? Was I being forced to invest to protect my rights? Did I remain the one true believer in an obviously forlorn cause?

In fact for one or two of these investments, if I hadn’t invested I would effectively have lost my rights/position. But in general my motivation wasn’t strictly financial. I invested, originally and subsequently, to support a friend of mine. I once had pretty high hopes for the business, but by month 22 I knew I wasn’t going to be dining out on this investment. Since then I’ve been investing amounts that I can afford, primarily because I’ve been asked to, and my relationship with the founder means I have wanted to say Yes.

In the meantime, there is no liquidity, no visibility, and no reward from this investment. Just the occasional moment of dread when a shareholder update lands in my inbox.

The dream machine

More positive, on the face of it, is the type of business that I am calling here a ‘dream machine’. This type of business, illustrated below by company S, appears to be doing brilliantly. On paper, my investment in company S is showing an internal rate of return (annualised return) of over 100% per year, over 5 years! In theory my initial investment of £50k is now worth over £1m.

I say “in theory” because the only basis for the valuation of company S is the paper valuation it is claiming based on recent investment rounds. As you can see below, I did not participate in any subsequent investment rounds. And as anybody who has followed WeWork’s recent fall from grace can see, paper valuations set by venture capital investors may not be grounded in reality.

In practice, the most obvious next step with company S is a brutal return to reality. Investors will be asked to cough up more cash, or lose their exposure almost completely. If I’m not prepared to throw good money after bad, my bad becomes terrible.

As I said, angel investing isn’t for the faint hearted.

VC Plod

My last example is also a relatively common example.

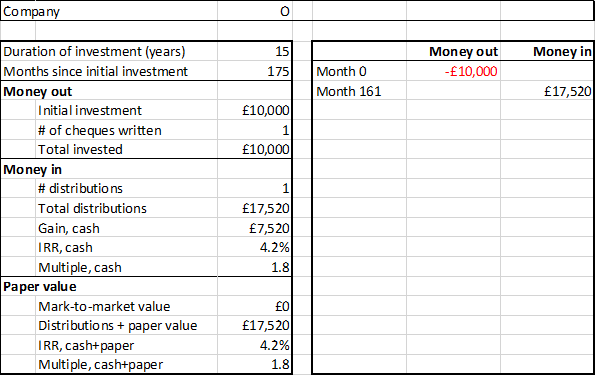

My money went in many moons ago, along with a very prestigious venture capital (VC) investor. Many, many moons ago. 175 moons ago, in fact. This was a very promising business, already profitable, which appeared likely to skyrocket to a mega IPO. In practice the controlling shareholders had very different ideas, and a lot of internal shareholder squabbling resulted. At some point many of the investors decided they wanted to sell their investment, but there wasn’t a way for them to do that either. We all waited, and waited. Ultimately, we achieved an exit. After 15 years, at less than 2x our money. That rate of return – 4.2% – is lower even than Zopa/FundingCircle.

The grim reality of angel investing

The examples in this blog are real, admittedly with company names/dates/etc hidden to preserve confidentiality.

The examples here are not uncommon. If you speak to an experienced (10+ investments, 10+ years) angel investor, he/she will recognise more than one of these examples.

What these examples illustrate you is several uncomfortable truths about angel investing:

- You have no liquidity. There is usually no ability to choose when to exit an investment. You may be able to choose whether to sell, but you may not – as was the case in company T.

- Your initial investment may prove to the first of many. If you fall in love with a business, and want to clear out your live savings to buy as many shares as possible – you are an idiot. Especially if it comes back asking for more, and if you don’t cough up you lose your existing rights/position.

- It take ages. Many, many moons. You won’t know whether you are any good for at least 10 years. Even if you luck out or bomb out in the first 3-4 years, you can’t form a view on your performance for 10+ years.

- Your millions won’t buy champagne. Your stake may appear to be worth gazillions – it may actually be worth gazillions – but without liquidity there is practically nothing you can do with it. Champagne bars will not accept your paper shareholdings as currency. And, more often than not, your incredibly valuable stake will turn out to be worth quite a lot less than you first had indicated.

- You can obtain these returns in the public markets. If you manage to invest early on in an Amazon, an ASOS, a Microsoft, a Fever Tree, an A2 Milk, etc you can achieve returns that would make most angel investors blush.

- Just one pinch-yourself-amazing investment can make you enormously rich. My biggest angel investment is £100k. If only I’d put £100k into company A, and held on all the way to exit, I’d have made over £6m on that investment – which would have been several times more than my total ever amount invested in angel investments. Too bad I didn’t.

Such a fantastic post with some great examples! Trying to work out the redacted companies …

LikeLike

This is an excellent article Fire V London, you rarely see concrete numbers being turned up by angel investors. Have you considered doing a total portfolio IRR for your angel investments as a whole?

Being a financial blogger of more humble means, I’ve been scratching my itch with (I know, I know, and I think you do as you read my article, too) crowd funding type investing in private companies. It started as a one-off, then a two-off, and I’m now up to 40+ investments. They’re nearly all very small investments (a couple of outliers) but the total invested has inched up into a meaningful if still very modest % of net worth, even after tax reliefs.

My theory was working with less information than an angel like you (IIRC many of yours are into friends or companies you know via work?) I need to get to about 100 separate investments, to increase my chances of hitting a unicorn. I expect about 50% of these to return nothing to what I put in, biased towards nothing, with maybe 40% as a double or so, 5% as a decent multiple and 1-5% as multi-baggers that ‘return the fund’.

That might sound fanciful, but I’ve already hit my first (and last? 😉 ) unicorn. Sadly the small amounts I’m investing each time obviously limited the upside! And of course, as you say, I haven’t exited yet!

I am finding this kind of investing ever more engrossing though. I should probably consider a career change!

LikeLiked by 1 person

@TI thanks for the kind words. As you say I don’t think I have seen actual data blogged before so thought it was time to put that right.

One thing I have not done is do one holistic IRR for the entire portfolio. I should do it but my data tracking doesn’t lend itself to it so I haven’t. I do however know my total multiples – on cash and on paper+cash – and they are, these days, good on both counts – albeit after many many years. Nonetheless I keep my allocation to angel investing low because the poor liquidity / need to fund follow-ons really sucks.

I plan to cover crowd/EISfund/etc alternatives in an upcoming blog post, but the TL;DR is that I am afraid I don’t hold out much hope you will see decent multiples even with ‘unicorn’ crowd investments. One reason is that the incoming valuations are often far too high – far above what the ‘informed’ market would pay. So even if there is a decent exit the multiple will be 2-3x worse than it should have been. I.e. 30x becomes 10x.

LikeLike

Yes, I suspect you’re right for the category as a whole. (Of course I am *special* haha).

My best returner on paper is 17x so far but of course no exit yet. I am pretty confident I’ll get at least 10x out of it when it does exit.

But with that said, it is one of several successful companies being used by many new fund raisers to justify ever higher valuations today.

So your point about starting values is very pertinent, I agree.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And of course if your argument is that you need to have a portfolio of 100 to get a unicorn, and that unicorn returns you 10-20x, you are going to need to see pretty decent returns from your other 99 simply to get into the black.

LikeLike

“And of course if your argument is that you need to have a portfolio of 100 to get a unicorn, and that unicorn returns you 10-20x, you are going to need to see pretty decent returns from your other 99 simply to get into the black.”

True! Although there are some other mitigating factors (principally EIS and loss relief).

Also I wouldn’t say it’s an ‘argument’ (or solid expectation), it’s a first iteration rule of thumb I’m using, based on my reality. (I’d much prefer to be a financial services sector insider getting the inside scoop for the basis of angel/unlisted investing but I’m not! 🙂 )

But your points all stand and I probably wouldn’t be doing this like I am if I wasn’t mitigating it against some other non-financial returns stuff (gaining experience/*maybe* potential future job…)

On paper I am roughly 2x up on an after-tax-relief basis currently, but I don’t trust that at all and am discounting by 50% in my master spreadsheet. You could credibly argue that’s still too high.

I am only uprating holdings on new fund-raising / valuations, notwithstanding your very on-point comments about WeWork (and see also some Woodford valuation uplifts it seems.)

LikeLike

(Only just seen this reply, it landed in spam – doh!)

You are thinking about it the right way. However I think you are not backing the right things! My deals haven’t come from FS industry inside track, but a wide assortment of personal connections. Many later ones have come as a result of earlier ones. I suspect you know some backable folks so the key is to negotiate yourself a way in. Almost certainly that will be on better terms than the Crowdcube/Seedrs/similar will offer you.

Uprating on new fundraising valuations is pretty dangerous. I don’t however know a clearly better way of doing it. One way would be only pay attention to valuations where shareholders can *sell* – but there are not very many of these. Your approach of applying a discount is probably more practical.

Incidentally all my returns are quoted ignoring tax relief. Tho a couple of my examples are via fee-charging platforms/intermediaries so the returns I’m quoting there are net of fees.

LikeLike

Fascinating article. I’m sitting on the other side of the equation, i.e. the business trying to generate that return for the angel. I agree that its largely a patience game due to zero liquidity.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the article, incredibly useful. I wonder what tools/platforms you use to find angel investment opportunities? Are these the likes of Seedrs and Syndicate Room? Or is this through much more restricted (closed) angel investment clubs/groups? Thanks in advance.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Leonid – I plan to look at this in an upcoming post. TL;DR: I don’t put much value in any of the crowd/fund versions. My stuff has come from direct relationships. The London effect 😉

LikeLike

Nice post. For a while I was investing in a small way through crowdcube, seedrs and some other platforms. Thankfully I restricted these very speculative investments in total to about 1% of my investments. The majority (as you would expect) have either gone bust, are stuck with no chance of growing, pivoted and asked for more money [no, no, no] and one simply returned my original investment. The only ones that worked were two bonds paying good returns which also paid my capital back.

My lessons:

1. in retrospect the valuations of many were too high

2. this sort of investment should be for fun … and not to reply on too much

3. you have not control at all.

Adam

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have had an overall good result from angel investing but I stay away from it now.

A lot of the companies raising money on crowdfunding platforms are just money sinks and you get all the downsides of private equity (no liquidity) with the added bonus of losing your money at the end of it.

I also have almost as much money as I need so I don’t need to gamble what I have for more.

But, you seem to have a flair for this type of thing – so I’ll keep an eye on upcoming posts to see how you do!

LikeLike

[…] about angel investing. My first post looked at 10 Tips for new angels; my second post talked about what to expect of your angel investments. This post tackles a question that grows in importance as you build experience, and a portfolio, of […]

LikeLike

[…] discussed in my 2nd post of this series some of the different journeys an angel investment can follow. But what matters is the exit. While there are plenty of crowd investors these days, what are the […]

LikeLike