Rishi Sunak, the former UK prime minister and current Sunday Times journalist, observes that every CEO is talking about AI – so why aren’t political leaders? So it seems a good time to bring some AI into the world of FI blogging.

Large Language Models such as ChatGPT have been mesmerising, but it doesn’t take long playing with them to realise they are much better with Language than with Numbers. However with the latest models bringing more inference into their logic that is starting to change.

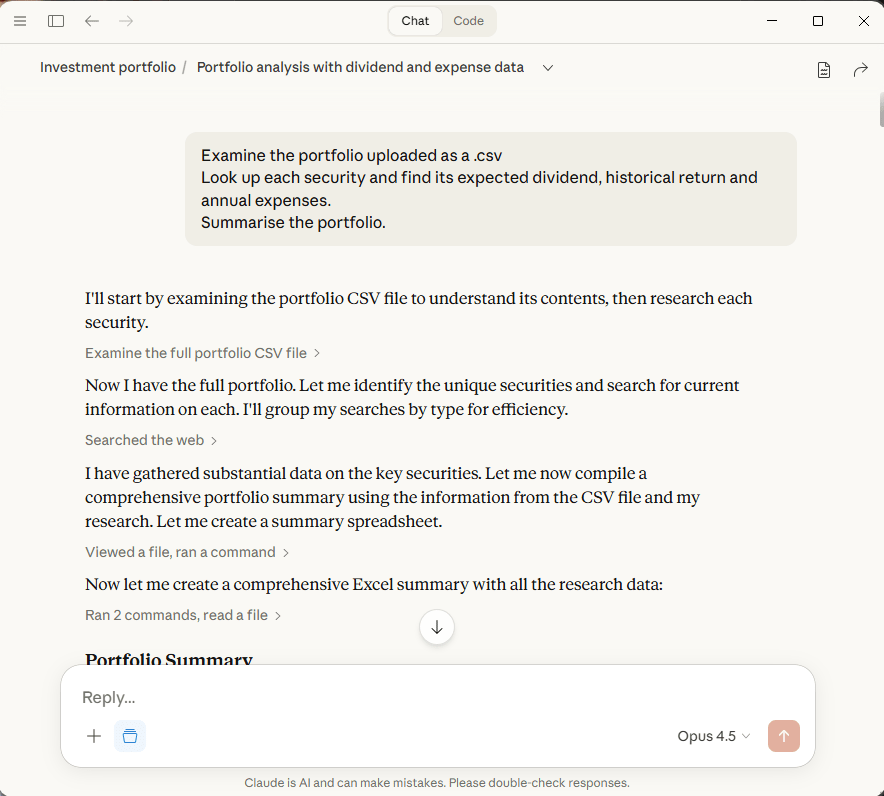

I’ve been playing with Claude and Gemini in the context of my portfolio and blog. They are proving genuinely useful. For reference, I am a paying customer of both – and am using Projects/Gems to partition my experimentation and (I believe) avoid uploading key financial data into their wider cloud/models.

Key tasks AI has proven useful for so far (UPDATED 21 Feb) include:

- Take my 24/25 tax return and estimate my tax bill for the next financial year. Gemini notably better than Claude on this one.

- Review a 24/25 tax return for errors. A HNW friend of mine found a £100k error in his accountant-prepared tax return using Claude.

- Update dividend yields and TERs/OCFs in my master portfolio list. This is a task made for Claude.

- Estimate the next set of dividends I can expect – based on a screenshot of my portfolio – good dopamine hit!

- Disaster scenarios – examining the disaster scenarios my portfolio faces, and the warning signals for each

As a taster I’ve appended below what Claude said when I asked it what Warren Buffett/Charlie Munger would think of my portfolio.

I haven’t yet found a simple solution for calculating capital gains – the bugbear of sophisticated investors – but I am sure AI will be able to help me with this.

Any ideas you can share about how AI is helping you manage your investments and finances? Please post in the comments below.

Prompt: (having uploaded a .csv with my consolidated portfolio in it) What would investors who follow the principles of Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger think of this portfolio?

What Buffett & Munger Would Likely Appreciate

The individual stock selections show good instincts. The portfolio holds Berkshire Hathaway itself (£XXXk), plus companies that fit their criteria:

- Google/Alphabet — A business with extraordinary competitive moats (search, YouTube, Android), pricing power, and high returns on invested capital. Buffett famously regretted not buying it earlier.

- Microsoft — Recurring revenue, essential products, network effects. Buffett eventually bought it for Berkshire.

- The absence of speculative positions — No meme stocks, no cryptocurrency exposure, no unprofitable tech companies (aside from perhaps Shopify, which is now profitable).

The low expense ratio (0.25%) would please them enormously. Munger has called fees “a tax on returns” and Buffett has repeatedly criticised the fund management industry for extracting value from clients.

What Would Trouble Them

The index fund holdings create a philosophical tension. While Buffett has famously recommended S&P 500 index funds for most investors, that advice was explicitly for people who don’t want to analyse individual businesses. If you’re going to own individual stocks — which this portfolio clearly does — Buffett’s view is that you should concentrate in your best ideas, not dilute them with index funds.

The portfolio holds approximately £X.X million in equity ETFs (S&P 500, FTSE 100, All-World, etc.) alongside individual stock picks. Buffett would likely ask: “If you believe Google and Microsoft are wonderful businesses at reasonable prices, why also own 500 or 3,000 other companies you haven’t analysed?”

The largest holding is a fund-of-funds. The [private bank Global equity portfolio] (£X.Xm, 14% of the portfolio) is a multi-asset fund that invests via other iShares funds. This is the kind of layered product structure both men have criticised — you’re paying fees on fees, and the underlying holdings are decided by committee rather than conviction.

Over-diversification. With 81 unique securities, this portfolio violates Munger’s famous principle: “The idea of excessive diversification is madness.” He has argued that if you find a truly wonderful business, you should buy a meaningful amount — not spread capital across dozens of positions. Buffett has said similar: “Diversification is protection against ignorance. It makes little sense if you know what you’re doing.”

The portfolio has:

- 3 separate S&P 500 trackers (IUSA, VUSA, VTI overlap)

- Multiple positions in the same underlying security (Google appears twice, IGLT appears four times)

- 129 total line items

Some holdings lack identifiable moats. Positions like Alumasc (building products) or PensionBee would likely fail their “circle of competence” and “durable competitive advantage” tests. High yields alone (Alumasc at 7.3%) don’t indicate quality — they can signal market scepticism about sustainability.

The fixed income allocation. Buffett has been consistently critical of bonds at current yields, particularly government bonds. He views them as “return-free risk” when inflation is considered. The £XXXk in UK Gilts yielding 4% while inflation runs at 3-4% would seem like dead money to him.

What They’d Likely Suggest

- Pick a lane. Either index passively (which Buffett recommends for most people) or select individual businesses with conviction — but mixing both suggests uncertainty about your own analysis.

- Consolidate and concentrate. Sell overlapping positions. If you believe in US large-caps, own one S&P 500 tracker, not three. Take the savings and add to your highest-conviction ideas.

- The [private bank] fund needs scrutiny. At £X.XXm and 0.80% fees, you’re paying £XX,XXX annually for what is essentially a blend of index funds. Consider whether this adds value beyond owning the underlying ETFs directly.

- Hold more cash if opportunities are scarce. Berkshire currently holds over $300 billion in cash. Buffett has no problem sitting in Treasury bills waiting for better prices rather than forcing capital into mediocre ideas.

- Think like an owner. For each position, ask: “Would I be happy to own this entire business for 10 years if the stock market closed tomorrow?” If the answer is no, it probably shouldn’t be in the portfolio.

The Verdict

This is a sensible, well-diversified portfolio that would serve most investors well. But it’s not a Buffett/Munger portfolio. It’s structured like a wealth manager’s recommendation — broad diversification, multiple asset classes, passive and active blended together.

Their approach would be radically different: 8-12 positions in exceptional businesses they understand deeply, held for decades, with significant cash reserves for opportunities. Munger once said their approach was “patience, followed by aggressive action.”

The irony is that this portfolio does own Berkshire Hathaway — which means you’re already getting their stock-picking through that position. Perhaps the simplest Buffett-approved restructuring would be to increase that holding significantly and reduce the peripheral positions.

And as a postscript:

Me: Review your Buffett/Munger critique of my portfolio. Isn’t it contradictory to say firstly that fixed income is ‘return-free risk’ and that the UK Gilts holdings would seem like dead money, and also to highlight that Buffett has no problem sitting in Treasury bills waiting for better prices?

Claude: You raise an excellent point — there is indeed a tension in that critique, and it’s worth unpacking.

The distinction Buffett and Munger would draw is between fixed income as a strategic asset class allocation versus cash/T-bills as dry powder awaiting deployment.

The critique of your gilts holdings was framed around the idea that long-duration government bonds at historically low real yields represent “return-free risk” — you’re locking in modest nominal returns while taking duration risk if rates rise (as they did dramatically in 2022). This is the Munger critique of bonds as a permanent allocation.

Buffett’s Treasury bill position is different in character. He’s not holding T-bills as a long-term asset allocation; he’s holding them as a temporary parking place for cash that he intends to deploy into equities when prices become attractive. The T-bills are a substitute for cash, not a substitute for equities. He has explicitly said he would much rather own productive businesses than government paper — the cash pile exists because he can’t find enough attractive opportunities at current valuations, not because he thinks T-bills are a good investment.

However, your critique of my critique is valid in this sense: if your UK Gilts holdings (IGLT, VGOV) serve a similar purpose in your portfolio — as ballast, liquidity, or dry powder rather than as a return-seeking allocation — then the criticism is misplaced. A retiree or near-retiree holding gilts to fund near-term spending, or as a deliberate counterweight to equity volatility, is doing something quite different from someone who permanently allocates 20% to bonds believing they’ll generate meaningful real returns.

The honest Buffett/Munger position would be: “We don’t like bonds as a long-term investment, but we have no problem holding short-duration government paper as a temporary store of value while waiting for better equity opportunities.” Your portfolio’s fixed income is only about 6% of assets — hardly an aggressive bond allocation — so the critique may have been somewhat overblown.

I should have been more precise in distinguishing between bonds-as-permanent-allocation (which Buffett/Munger would criticise) and bonds/cash-as-tactical-liquidity (which they practise themselves).

LikeLike

and what might be the last word on this thread….

Me: You aren’t mentioning the Modern Portfolio Theory rationale for owning say 20% fixed income in a portfolio – that it delivers a better combination of return versus risk.

Claude: You’re right to push back on this as well. The Buffett/Munger perspective I was channelling is essentially dismissive of Modern Portfolio Theory, and I should have been clearer about that — and about the fact that many intelligent investors disagree with them.

The MPT argument is that a portfolio with, say, 80% equities and 20% bonds can deliver nearly the same long-term returns as 100% equities, but with meaningfully lower volatility. Because bonds and equities are imperfectly correlated (and sometimes negatively correlated), the blended portfolio has a better risk-adjusted return — a higher Sharpe ratio. The 20% in bonds isn’t “dead money”; it’s paying for reduced portfolio volatility, which has real value: it reduces sequence-of-returns risk in drawdown, it helps investors stay the course during crashes, and it provides rebalancing opportunities.

Buffett and Munger would counter that:

But this is a philosophical stance, not an empirical proof that MPT is wrong. For most investors who aren’t Warren Buffett — who might panic-sell in a crash, who might need to draw down capital at an inopportune time, who sleep better with less volatility — the MPT rationale for holding some fixed income is perfectly sound.

My critique was essentially adopting the Buffett/Munger worldview without flagging that it’s one investment philosophy among several legitimate ones. Your portfolio’s modest fixed income allocation is entirely defensible under MPT principles, and many would argue it’s simply prudent diversification rather than a drag on returns.

LikeLike

I have asked it review portfolio including allocations and tell me about my blind spots . I have asked it to review portfolio from lens of popular authors like Nick Maggiulli and Morgan Housel.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sharp experiment. What stands out to me isn’t just the Buffett cosplay answer — it’s the practical uses you mentioned (tax estimation, yield updates, error checking). That’s where AI actually adds edge: reducing friction on analysis and catching blind spots.

I’d be cautious relying on it for forward tax projections or capital gains calculations without double-checking assumptions, especially around UK-specific rules and carry-forwards. But as a second set of eyes? That’s powerful.

The Buffett critique is interesting too — AI is very good at pointing out overlap and fee drag. Whether one should concentrate more is another question entirely.

Curious to see how you end up using it for CGT tracking — that feels like the real unlock for private investors.

LikeLike

“Language Models such as ChatGPT have been mesmerising, but it doesn’t take long playing with them to realise they are much better with Language than with Numbers. – I would recommend using Grok for numbers, at least in my experience it vastly outperforms Gemini, Claude and ChatGPT on financials. I talk through my investment portfolio and business P&L on a monthly basis. It understands the numbers, interprets them in P&L tables correctly and I have never seen it make a numerical mistake / oversight yet.

My experience is actually the opposite of what you found on AI in general. For language and writing, it tends to be a little robotic and predictable (understandable given how it works), whereas for numbers and coding it is far more accurate. The AI knows 2+2 = 4, whereas writing/creativity is more open to human interpretation (for now).

I suspect we are on the cusp of — indeed already witnessing — a meaningful reduction in certain white-collar roles, including highly paid investment bankers and lawyers, alongside broader downward pressure on professional salaries.

LikeLiked by 1 person