I’ve used portfolio leverage to help me buy two properties in the last 10 years.

To recap the most recent episode, very briefly, it goes as follows:

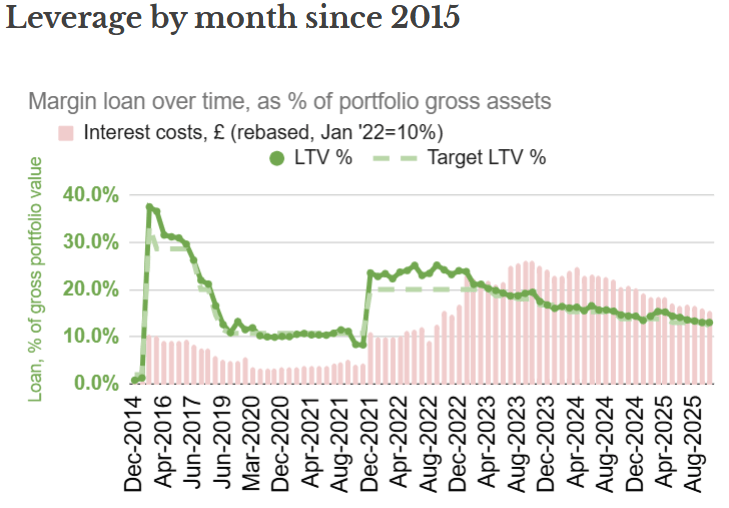

- In December 2021, I borrowed about 25% of my portfolio’s value to buy my Coastal Folly. I targeted reducing this to a 20% ‘loan-to-value’ (LTV) as soon as practicable.

- Only a few weeks later, Russia launched its full-scale invasion of the Ukraine. This disrupted the stock market, and energy markets. The energy market disruption led to a spike in inflation, which caused central banks to hike base rates. It also caused my LTV to go up, not down.

- I steadily paid off a bit of the loan, but the higher rates meant that my interest expenses went up 2.5x over the following 20 months.

- Since then however my portfolio has gained in value, and my loan has reduced, leaving it today at about 13% of the portfolio value. My interest costs are about 1.5x the January 2022 starting point, which is mildly annoying but very manageable.

- I’m left feeling firmly under control, with a relatively low level of risk. The two key risks that I need to consider are

- a hike in interest rates – which feels very unlikely

- a plummeting stock market – this feels a lot more likely, particularly in October 2025. But with my loan being only 12.5% of the portfolio value, even if the portfolio suddenly halved in value (a very rare and unlikely scenario) the loan would still amount to only 20% of the reduced portfolio value.

This leaves me wondering what the long term idealised level of leverage is for my portfolio.

Disclaimer

I should say before I continue that I strongly discourage readers from trying any of this at home. For almost everybody, the right level of leverage is: zero. I have a level of financial knowledge and confidence that is unusual; on top of this I have a secure financial situation with a variety of assets both in my investment portfolio and outside it. There are very few people in the UK who share my combination of financial strength, knowledge and psychology. I share my thinking as much for my own benefit – to get my thinking straight – as for yours. Feel free to learn or laugh, but do not copy.

What’s the point of leverage?

First of all, let’s just restate the case for using leverage.

At its simplest, it’s that my portfolio has returned a long term average gross return of 9%. Even at current interest rates, my leverage costs around an average of 5%. If you can borrow at 5% and make 9% it’s Game On.

[Update: Of course it isn’t that simple, because while the 5% figure is stable and predictable, the 9% returns are volatile – in fact in the 12 full years since I’ve been tracking my portfolio month, no year has returned 9%. My years since 2013 range from +24% to -22%. But because I know I have a variety of other assets outside my investment portfolio, and I am usually not depending on any of my investment portfolio for living expenses, I am taking the long term view of these figures. My compound annual returns very rarely drop below 9% p.a.]

However tax screws this up, because my effective tax rate narrows the delta considerably. Individuals in the UK can not deduct interest costs (whether mortgages or otherwise) from their taxable income. And high earners like me face a marginal tax rate of 45%. At that tax rate, a gross return of 9% becomes a net return of under 5%, and my interest expenses leave me out of pocket.

In fact thank goodness my effective tax rate is a lot lower than 45%. In effect it is no more than 30%, because:

- Consider only regular, unsheltered accounts. I’m ignoring tax sheltered accounts like pensions and ISAs. In point of fact, leverage is anyway difficult/impossible to use in pensions and ISAs.

- (Note – there is a useful special case of a Ltd Company, which I do use for some of my investing; Ltd Companies both have a lower tax rate and *can* deduct interest expenses, so any argument I make for borrowing as an individual applies more strongly to a Ltd company investment portfolio.)

- Assume an average total gross return of 9% per year. My 12+ year average is currently 9.6% p.a. though obviously years vary enormously.

- Now break down this return into its two key constituent parts:

- Dividend income. I am assuming my dividend yield is around 3%. I also assume I am paying 40% tax on this (a blend of 45% on some, and company tax on the rest). 40% of 3% is 1.2% – i.e. 1.2% of my unsheltered portfolio a year is going on income tax. It’s worth remembering that even in very bad years, dividend income still happens – in fact dividends are remarkably stable even when share prices are collapsing.

- Capital gains. The rest of my ~9% return, 6.5%, is from Capital Gains. Assume I am paying 24% on this, i.e. 1.6% of my portfolio a year is going on CGT. This assumes I realise capital gains, which in general I don’t.

- Totalling the two tax bites out of my returns sums to 2.8% out of 9%. This makes about a 30% tax rate, and leaves 6.2% of net return. So I am winning vs a 5% cost of funds, but not by much. However to the extent that my capital gains are unrealised, which most of them are, then I am winning more.

So, on balance there is a case for using (modest levels of) leverage even at current interest levels. In practice, as I said above, some of my leverage is deductible and there are other advantages to leverage; so there is a slightly bigger win than these numbers suggest. And if interest rates fall, which looks likely, then the advantages increase.

First principles

Based on the argument so far, it feels like the optimum level of leverage probably depends on three things:

- Interest rates.

- Interest rates are currently a little bit higher than the medium term history.

- The direction of travel is down. However we are unlikely to refer to the near zero levels of five years ago.

- Taxes. I’ve set out above the approximate levels of tax we’re enduring in the UK. This hasn’t changed too much over recent years, but one can’t ignore the possibility of radical changes, such as

- Aligning capital gain rates with income tax rates

- Charging National Insurance (the UK’s social charges) on investment income, which would put income taxes up by 2-11%

- In the extreme, charging some form of wealth tax – e.g. taxing unrealised gains.

- Portfolio volatility:

- My portfolio’s maximum drawdown since January 2013 has been 23%. The ‘maximum drawdown’ is the most it has lost, peak to trough, on a monthly basis during that time period. One might reasonably assume that the daily drawdown is slightly worse, but I don’t track that.

- VWRL’s maximum drawdown (daily) since inception is 26%. I accept that VWRL is a close proxy for my portfolio. Its inception is actually similar to this blog – I have data for it since 2012.

- The S&P’s maximum (daily) drawdown, according to Google, was either 57% in 2007-2009 or 60% from 2000 to 2013.

- My portfolio is a bit more diversified than being purely S&P, but one might reasonably assume I need to be able to withstand a 50% drop in gross portfolio value.

- It is hard to know if my volatility changes, so I generally treat my portfolio’s volatility as a constant, if you can get your head around that tautology.

So, with those principle’s established, how do we set a target for a leverage level?

Option 1: Psychological target

Let’s start with the emotional angle. The cognitive bias. How might my family react if they suddenly have to pick up the pieces after some dreadful tragedy wipes out me and Mrs FvL in an instant?

Is there just an upper limit on what I should borrow? I have borrowed more than £1m via margin loans. That’s a lot of money. In theory I can imagine borrowing more than £10m. What amount is too much?

Or maybe the interest bill is something to apply a cap to? In summer 2023, I was paying more than £100k of interest. Out of post tax income. That felt like a lot. How would I feel paying >£1m a year of interest? Gulp.

If I had a £100m portfolio, would I have a problem with say £10m loan, and £500k annual interest charges?

It isn’t easy to be sure, but I don’t think I would have a problem with any of the levels above. So I don’t think the psychological / emotional approach holds lessons for the right level of leverage for me.

Option 2: An asset-based target

A maximum leverage level based on the amount of assets feels like the next place to turn. Ultimately this is how the lenders limit margin loans.

What’s the limit for margin loans?

The limit matters for two reasons. Firstly, it is the maximum you can borrow – always a useful number to know. But secondly, because unlike mortgages your loan is not completely under your control – and the closer you are to the limit, the less control you have.

I have two key margin lenders. One is a private bank, whose limit is they’ll lend you up to 70% of the net asset value. The other is Interactive Brokers, who lends 50% of total assets. This sounds more restrictive but in practice it has the effect of lending you 100% of your net assets, assuming you use all the borrowing to buy more assets (and not withdraw for other purposes, such as buying other assets outside the platform).

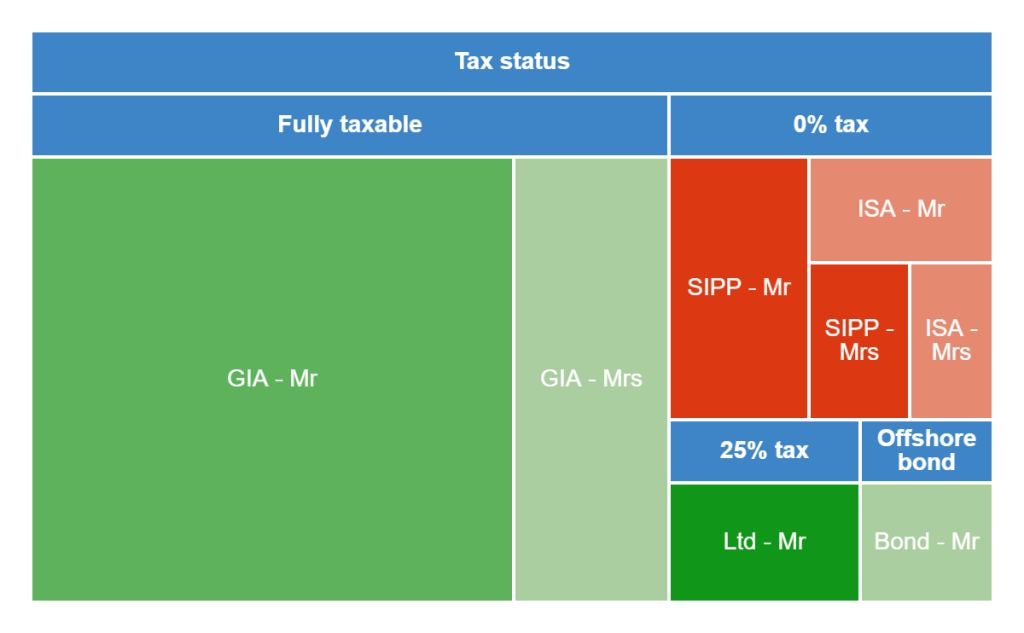

However these lending limits aren’t the whole story, because not all my portfolio is available for collateral:

- Let’s ignore the tax-free assets, SIPPS and ISAs, which are around 20% of my investable portfolio.

- Let’s ignore Mrs FIREvL entirely, even though her General Investment Account throws off a reasonable amount of income and is unencumbered – either by tax shelters or leverage.

- Let’s ignore my legacy offshore bond, where I am able to withdraw 5% a year for twenty years tax-free, though after that all gains (whether capital or income) are taxed at my marginal rate.

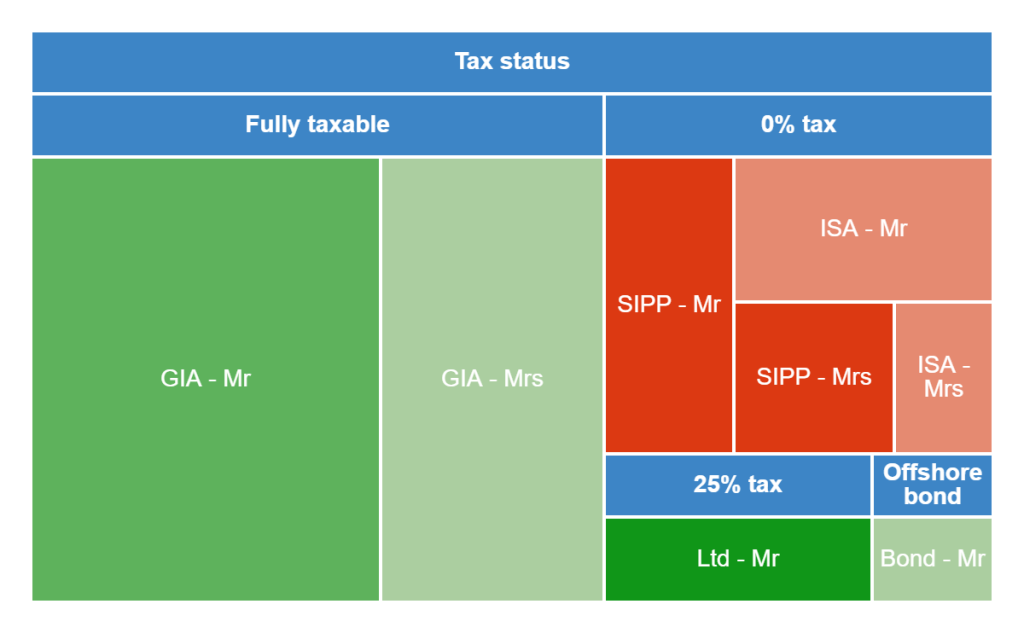

That still leaves a lot of headroom. My General Investment Accounts (GIAs) and my Ltd company between them (the darkest green bits in the image below) have about 55% of my investable assets in them.

So one approach would be to limit my loan to the tighter constraint of my two margin loan providers, which is a 50% lending limit against the gross portfolio, which effectively lets you double the size of the portfolio. If I applied this purely to the dark green zones shown above and assuming that these dark green zones are half of my investable assets, then my maximum loan would be 50% of the value of my (pre leverage) investable assets.

At that point, my maximum Loan To Value (LTV) would be 33% (because I’d use the loan of 50% to buy more assets – so for every £100k of net assets I’d borrow £50k and buy £50k more assets, at which point the £50k loan is 33% of the £150k gross exposure).

This calculation above takes into account all investable assets, whether owned by me or Mrs FireVLondon. In my blog I have discussed in general terms how I manage our assets collectively, and make sure Mrs FvL holds enough of our collective assets to be tax-efficient. But in general when I discuss performance, LTVs, and so on I am only analysing my portion of the pot. Mrs FvL’s portion tends to have a similar allocation, and perform similarly, but she has no leverage in her accounts.

To make the 33% LTV number comparable with other uses elsewhere in my blog, I need to convert it into a me-only LTV. If for instance my gross assets were about 75% of our total investable portfolio, so a 33% overall LTV would equate to a 40% LTV for the assets in my name.

When I bought the Dream Home in 2016, back in the era of low interest rates, I was briefly at a (personal) LTV of almost 40%, admittedly where I knew I had a significant windfall expected shortly. And then when I bought my Coastal Folly in 2022 I started at about 22% LTV and then after the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine my LTV peaked at just over 25%. These levels were uncomfortable, but manageable.

Ultimately however while I may have used quite high levels of leverage for specific periods of time, these limits aren’t much of a guide to a long term ideal level of leverage. An ideal level of leverage wouldn’t need much attention, and would be resilient to a sharp drop in the portfolio value. I wasn’t in that position after interest rates spiked and stock markets slumped in 2022/2023. There was nothing ideal about that level of leverage.

So, the maximum limit isn’t helping me answer the question.

But for a sense of what the professionals do, we could look at public equities. Blue chip companies tend to borrow about 10%-20% of their entity value. For instance, I took a quick look at P&G (about 10%, stable over 5 years), Exxon (15% in 2020, now 5%), Unilever (20%, stable over last 5 years). Debts of these levels leave them well away from any limits that would be uncomfortable. But in fact these three firms’ debt levels haven’t shifted much with interest rates – which doesn’t feel that intuitive to me. So leverage in the broad range 5-20% of portfolio value feels like it has a precedent, but I’d like something a bit more specific.

Option 3: Income-based limits

While margin lenders use asset ratios, let’s consider mortgages.

Mortgages to limit based on the asset – e.g. 90% of the house value. But the limit that really matters is the limit based on the income. Historically, with base rates much higher than today, UK mortgages were limited to about 3x income. These days of lower interest rates have seen multiple increase, but they are still income based – up to say 5x a joint income.

Another type of loan to consider is how much a private equity investor can borrow to buy a company with. Lenders here usually lend a multiple of the EBITDA of the purchased business. The multiple varies over the cycle but is often in the range 3-7x.

So, how would an income multiple work?

One approach would be to treat my margin loan as a mortgage, and say the optimum level for a loan is based on my earned income. However this is a FIRE blog and my whole psychology is to avoid needing to earn my living, so I don’t like this idea very much!

But what if I used my investment income instead? Would it be of my entire investment portfolio, which yields about 3.1%? If so, a 5x multiple would be a loan of about 15.5% the portfolio size, which by the time you’ve reinvested the loan means an LTV of 13.4%. Notice too that the income I’m using as a guide will itself increase as I borrow more money – something that doesn’t happen with mortgages or Private Equity borrowing!

A slight refinement is to limit the applicable income to that from the GIA plus Ltd portfolios. This is more obvious – both are leveragable – and their income amounts to about 1% of my total portfolio. So on that basis my loan would be about 5% of the total portfolio, and an LTV of a bit less.

The problem here is that it a simple rule like 5x the leveragable income makes no allowance for cheap rates versus expensive rates. I could flex the rule a bit to say ‘with higher rates, the multiple lowers’, but that feels quite subjective.

So, I’d prefer to think about something to do with interest rates. When money is cheap, I want to borrow more of it. When money is expensive, I don’t want to borrow.

Option 4: Limiting the interest cover

This option has elements I’ve seen before in commercial mortgages – it looks at the interest cover. I.e. what is the ratio between the leveraged income, and the interest expenses?

As I said above, the GIA/Ltd’s yield is only 1.2% of whole portfolio. Though the GIA/LTd are over 50% of my total assets, they are more like 45% of the total income (which amounts to 3.1% of the portfolio).

Plucking a number out of the air, I could look for a 1x interest cover. But this would leave me out of pocket after paying dividend taxes.

At a 2x ratio, I could just about cover taxes, but I’d have precious little free cashflow to reinvest or pay down debt. At 2x ratio, my current loan would need only a slight reduction. I.e. LTV down from 13% to about 10%. At which point interest expense (at 5% rates) would be 0.5%, and my GIA/Ltd yield would be twice that, pre tax.

At a 3x ratio, I could cover taxes and still have some free cashflow to reinvest and/or repay debt. This feels more comfortable. To hit a 3x ratio, I need to get my current interest expense down a reasonable clip from what it is now.

And GIA/Ltd income is 45% of total income, or a bit more of FvL; in fact yield is around 1.4% of FvL total. i.e. 3x 0.45%or 2x 0.7%.

And as interest rates drop, LTV would go up. If my margin rate fell to 3% for instance, and my 1.4% yield had to be 3x my interest costs, then I could afford interest of about 0.45% – and I could have LTV of 15% – a bit higher than my current level.

Concluding: my ‘silver rule’

I am going to head for the following ‘rule’ for my long term leverage amount: I want my leveraged accounts’ interest expense to be no more than one third of my leveraged accounts’ income.

With recent interest rate cuts, I am close to my silver rule. Currently my interest expense is about 10% too big to meet the rule. If interest rates don’t change, my LTV should be about one tenth lower, and I’ll carry on paying down debt until it reaches that level – about 11.7%. But if interest rates drop just a little more, I may well have met my ‘silver rule’.

While my blended overall sustainable LTV might be around 12%, for incremental gains in my leveraged portfolio, the incremental LTV is higher – it is around 25%. Assuming no change in interest rates, if I had a £1m windfall land in the leveraged account, my loan ought to increase by about £250k, allowing me to buy £1.25m of assets. The extra interest expense would be about £12.5k. And my dividend income would increase by around 3% x £1.25m = £37.5k – three times the interest expense. This means that another way to meet my silver rule is to see the leveraged portfolios grow in value.

I am calling it a ‘silver rule’ because I have not honoured this rule since buying the Coastal Folly in 2021.

I also want to avoid the temptation to load up the portfolio with income-generating holds, to hit the leverage rule. So I am not honouring the rule with the ‘golden’ moniker.

Most importantly, the point of having a conservative borrowing approach is to avoid being forced into disposals. The harder the leverage rule, the more it forces selling. A sharp drop in the market will reduce my portfolio, and increase my LTV% – and I need to be able to ride that out without panicking. So the sustainable borrowing metric is a long term metric, not a short term metric.

Aiming to borrow at a level that I can cover the interest costs threefold from income feels like a reasonable aim that matches how I manage the portfolio, will enable me to pay down the debt gradually in a market downturn, would leave me with fairly low LTVs that would be resilient to sharp market drops, and will give my long term returns an appreciable fillip. I’m happy to work towards that.

Any reactions, comments or questions on the above would be useful for me. Am I crazy? Overthinking it? Running risks I don’t realise? Paying too much for my debt? Or should I just get out more?

Obviously you should get out more…

You hit the problem early on: 9% return (only?) with 5% costs suggests all you can eat buffet until the manager tells you to leave (50%/70%! ltv).

But the 9% (6% net) isn’t a point value, but is a distribution that comes with a variance. The 5% similarly with a smaller one that isn’t independent. Your first question is what does your return distribution look like across the distribution of the difference. If there’s a 50% drawdown, being leveraged looks like a bad deal (although rejoice in the CGT shield!). Not drawn it, but I suspect while most of the distribution is mostly above zero, there’s a lot of it quite a long way below zero. Sure the average is (was) 1% positive, but are these now pennies in a suspiciously steaming about-to-be-rolled road?

Another way to think about this is asset allocation, where the loan acts to shrink your bond portion negatively. With 20% leverage, a 60:40 appears to be 80:20. If you think there is a better than even chance of a significant drawdown in the next two years, are you committed to this level of equity allocation without any defensive posture? At least the 3x dividend cover argument means that you can remain committed to this allocation through the crash and out the other side, and that should be the primary concern for the overleveraged gentleman of distinction.

I suspect the income/growth division and the tax dog-tails are wagging too hard here and the conclusion of the silver rule is close enough to a small belt tightening from the current position that it looks attractive as a solution. There are very good reasons why the GIA might wish to fly to dividends defensively right now (you can get 9% yields if that is all you are asking for from VWRL), and you wouldn’t want that to result in more leverage / less belt tightening.

I would look at leverage in two ways – one being a very useful short term cashflow boost to buy nice assets. A rule there required to pay down over a cycle. And secondly a way to move allocations over 100% equities. A greed lever. Not one I’d pull when fearful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think you’re over-complicating a lot.

Comparing a highly uncertain 9% return with a certain 5% cost is unwise. You need to risk-adjust.

I also think you should ask yourself why you both borrow and invest in fixed income. Unless you’re deliberately trying to engineer a yield curve position (own 10 yr bonds funded with 3 month money) I don’t think this makes sense at all.

You should compare your near-certain 5% cost of leverage not with the uncertain 9% return of your equity allocation but with the near-certain 5-6% return of your fixed income allocation. And that will make it obvious that what you are doing with leverage doesn’t make sense.

By all means use leverage to cover liquidity needs (like the folly). But otherwise reduce leverage to zero by selling down fixed income.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Tom – that is a very fair challenge.

I remember amateurishly learning about Modern Portfolio Theory once tho and my takeaway was that there is a difference between a portfolio at 100% equity, 20% fixed income, -20% loan, compared to 100% equity. Slightly better risk/return balance with the diversified approach.

I’m quite prepared to believe I misunderstood or that the taxes/costs etc outweigh the smoother result but I haven’t done the analysis.

LikeLike

@Tom – so if you could earn 8% cash dividend (say) from HY, would that be acceptable to offset the leverage debt at 5%?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Probably not. Is a risky 8% gross better than a certain 5% net?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hmm, have been running an interest only mortgage alongside a HY portfolio in an ISA yielding c.10% all in for a while now and was looking for someone to tell me I wasn’t bonkers…maybe Fire vs London would be more supportive 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Generally I don’t like high yield portfolios, though I concede that my ‘property’ portfolio is tantamount to one.

Are you paying the interest out of the ISA dividend income? That feels a waste of future year’s compounding.

LikeLike

I am but I have FIRE’d already. Leverage on all my investments doing this is c.11%. I have identified the HY element against the debt specifically for its cash flow though in total the HY pot is over twice the size. So am using the debt to juice my income and it is to be repaid once I get to my 25% tax free pension; doing this helps with me not running down my ISA balances so I retain the tax free income in the future.11% feels sustainable and worthwhile at this time, if the HY market stutters more I may blink and repay it….

LikeLiked by 1 person

“What’s the ideal level of leverage?”

42

LikeLike

apologies if a stupid question, but the pink bars in the first chart, they aren’t the % interest you are paying on your loan are they? They seem too high, but there aren’t any other units (that I can see)

LikeLiked by 1 person

scratch that question, it’s £ in interest costs, which is a function of interest rate and loan size. Units not marked, but still useful to see just how much things have varied over the time period.

LikeLiked by 1 person

@Rhino Correct. Its £, units not shown, but indexed to a perfectly affordable number just after I drew down the loan in January 2022. That level is shown as 10pc, everything else is relative

LikeLike

I am thinking the same way as you do, but with mortage on my primary residence instead. Currently a 30% LTV on my investment portfolio composed of 80% equities and 20% interest. Retirement is separate.

Thinking of keeping 30% loan, but moving towards 70% equities. Yes, it makes sense. It provides liquidity and allows more money invested in equities. It dampens volatility. If I repaid the loan I would not be 100% equities.

Is it worth it? So far yes. Time will tell.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What about using leveraged etfs like WGEC/WTEF rather than a margin loan? Better Sharpe ratios, they pay lower leverage costs, better tax efficiency (leverage costs come out of income before distribution), no risk of a margin call, and overall less hassle!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Last time I looked, some time ago, leveraged ETFs performance was only valid on a short term basis – not many months at all. Has that changed ?

LikeLike

These ones are rebalanced quarterly so are suitable for holding long term – unlike the daily rebalanced ones that aren’t. Also they use lower leverage – 1.5X compared to 2-3X on the daily resets. The theory is that a 60/40 equity/bond split has a better Sharpe, so if you lever up 1.5X to an effective 90/60 you get equity like returns (or better) with lower volatility/drawdowns. Finally, they aren’t expensive – 0.20-0.25% (though leverage costs are within the fund and on top of that).

Three available in the UK from WisdomTree – Global (WGEC), US (WTEF) and European (NTSZ).

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree with previous comments that it makes little sense to have a GBP fixed income position while taking out GBP loan especially if you cannot write it off taxes.

Why don’t you borrow in CHF or JPY and buy assets in those currencies (not a widow maker carry trade). You can also hedge the FX if you wish. Run some screeners on Japan and you will find a tremendous amount of absolutely ridiculously good value small and mid cap stocks that buy back shares and pay a 2%+ dividend covering the margin cost and then some. Less value in CH market but some steady safe stocks there if you look hard enough. AVI Japan Trust in the UK is a good starting point for research into Japan, activism & M&A happening now and all the corporate governance that the TSE exchange is forcing companies to do.

I do not go over 15% margin loan to gross portfolio value. I’m comfortable at ~10%.

I would strongly suggest you model your portfolio’s drawdown to *more* than SPX (65%+DD on a daily) especially if you hold single stocks as well and a broker level margin increase during VAR shocks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] being used to pay down my portfolio loan. This actually leaves me underleveraged versus my ‘Silver rule‘ (which wants the interest expenses to be less than a third of the income in the unsheltered […]

LikeLike