This post is in an occasional series of blog posts (starting here) examining angel investing and the role it plays in high net worth peoples’ investment portfolios. This post looks at the ‘angel investing goes mainstream’ route of investing via crowdfunding platforms, drawing on an exclusive survey I ran on my blog.

I’m dealing here with equities – buying shares in companies – though most of my arguments would apply to crowdfunding platforms offering ways to invest in property, loans, and other asset classes.

There are numerous ways for the crowd to invest

These days, the budding angel investor with a couple of thousand in spare cash has a few crowdfunding platforms available to find ‘angel investments’ online. The obvious ones that jump to mind include:

- CrowdCube/Seedrs. Arch rivals now merging, both CrowdCube and Seedrs offer similar propositions – online marketplaces where early stage company raising capital can meet retail investor with capital. Both have decent scale, a wide diversity of sectors/businesses, and reasonable websites.

- Syndicate Room. I’m not sure how big the Syndicate Room crowdfunding site is but it has crossed my desk a couple of times; its USP was that it relied on a ‘recognised angel’ (my words, not its) to set the terms/price. This makes sense to me – as we’ll discuss below. However I don’t think Syndicate Room ever managed to achieve the sort of scale CrowdCube/Seedrs achieved and, in any marketplace game, scale is key.

- Angel List. Angel List is a different formula, but one that has a lot of appeal to me. AngelList allows experienced angel investors to ‘publish’ their dealflow, and other people to ‘follow’/join in. The lead angel gets some ‘carry’, or percentage, of any followers’ return. In theory this approach works for me on lots of levels, but in practice it never has.

What does the investor crowd look like?

While my blog audience is not necessarily a random sample of the crowd, it is nonetheless a revealing sample. And it turns out that my audience has quite a bit of experience of the crowd. Based on a survey of my readers that I did in Q4 2020, and filtering results onto the 241 respondents in the UK, it appears that:

- Crowdfunding is popularising angel investing. 33% of my UK respondents have experience of it. This is not heavily skewed by income level or net worth (though I suspect my blog is self selecting enough!). However crowdfunding is concentrated in those under 45 years old. By contrast, only 12% of respondents have made any angel investments directly, and this is noticeably skewed towards those earning £100k+ (even more so for those earning £300k+) and with investment portfolios of £750k+.

- Most angel investors are avoiding crowdfunding sites. Of the 29 investors in my survey who have made direct angel investments, the majority have not tried crowdfunding. And the vast majority (83%) of crowdfunders have not done any direct angel investments.

- Most crowdfunders have just made a few investments. A third have made only a single crowd investment. Another 41% have made 2-4. Only 2% have made 20+ investments.

- Crowdfunding investments are usually very small. Over half of investments are under £1000. Another 16% are less than £2000. None of my respondents appeared to have made an investment of £20k or more.

- The most popular sectors (of my audience) are Fintech, Food & Drink, and other Tech. Manufacturing, Retail, and Services don’t get much of a look in. My audience cites investments in, among others, Brewdog, Monzo, Freetrade, Money Dashboard, PolySolar, Sourced Market, Curve, Just Park, Taylor St Barristas, and a couple of breweries.

However, the crowd’s returns suck

I discussed in my 2nd post of this series some of the different journeys an angel investment can follow. But what matters is the exit. While there are plenty of crowd investors these days, what are the crowd exits looking like?

The short answer is that they are far too few and far between. While the crowd likes to celebrate the very occasional iconic successes, like Brewdog (which was in fact acquired within months of its crowdfunding round), the reality is that there are, all these years later, effectively no ‘home run’ venture exits to talk about. I would love to be corrected in the comments here but I don’t think I am going to be. By home run, I mean significantly more than 10x – let’s call it above 15x the money invested.

Of the crowd investors in my survey, 80% of them have never had any exit at all. A further 10% of them have had money back, but no more than they invested. Only 10% cite any form of gain.

Bear in mind that backing startups/etc shares at least one trait with gambling – you only remember the winners. My survey question was leaning in on the good news. My survey wasn’t asking “what has happened to your average investment” or “what are your average returns” or “what portion of your portfolio has seen an exit”. Instead, my survey was saying “Have you ever had an exit?” (emphasis added in this blog post).

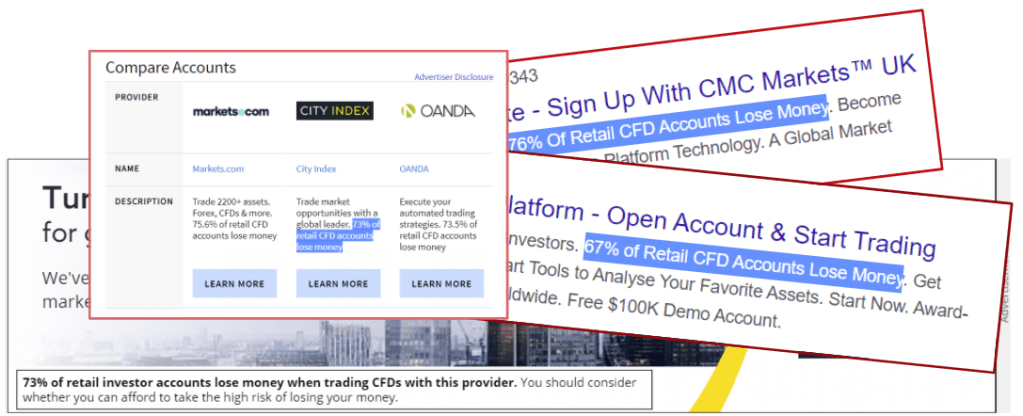

So, at this point in proceedings, crowd investing is doing worse than those spread betting firms that the FCA forces to put cigarette-style warnings on their packets:

Now, I am the first to argue that what angel returns need above all else is time. It took 7+ years for my first angel investing profit to appear, even on paper. The crowd isn’t that much older than that. Crowdcube was founded in 2009, Seedrs in 2012. But 2009 is in fact 12 years ago. Are these crowd investors prepared for 12 years?

Perhaps my crowd investors are unlucky. That seems implausible. I have the highest respect for my blog audience. One of my respondents has done more than 20 crowd investments but has never had any exit at all. Are they just unlucky? Really?

Or, perhaps, crowd investing is like the riskiest form of venture capital – where most investments lose money but the occasional unicorn generates all the returns. I confess my survey’s best outcome was ‘a gain of 5x or more’, which prevents me distinguishing between 6x and 16x. But only 2.5% of crowd investors claim to have seen a ‘gain of 5x or more’. These guys had both done quite a few crowd investments – more than 20 in one case – and they also done direct angel investing alongside crowd investing. I don’t know for certain that they haven’t seen a whopper >15x exit from their crowd funded portfolio, but I suspect it. I strongly suspect it.

So, based on my dataset – which is probably one of the largest datasets outside the customer databases of the crowdfunding platforms themselves (and they aren’t sharing!) – the picture is pretty clear. You might get >5x returns, less than 3% of the time. You might double your money, or halve your money, about 15% of the time. But 80% of the time you won’t get the money back. In fact 80% of folks, with an average don’t appear ever to have got any money back. Still holding out for those tasty early stage, angel / VC, ‘next big thing’ paydays? Sorry to shatter those dreams, I really am.

Why crowdfunding returns suck

There is a very good reason why crowd investments deliver terrible returns to crowd investors. Most investors who appreciate this reason stay well clear of crowdfunding platforms, and probably aren’t reading blog posts like this. They know the design of the crowd investing process is not there to deliver investor returns.

If you’re still reading this blog post at this point, it’s possible you haven’t understood the key process point that results in poor investor returns.

The underlying cause of the poor crowdfunding returns is that the crowdfunding process is massively asymmetrical, in the company’s favour. For instance, whereas investors pay fees of 1.5% of the amount invested, the company pays 7.75-8.25% of the amount invested. This asymmetry results in poor returns for at least two reasons.

Why returns suck 1: The Entry sucks

The crowdfunding process is tilted firmly in favour of the company, and this is most obvious at the point you first invest. The valuation is not negotiated ‘by the market’. It is, basically, set by the company. The platform will argue that it will be tested by the crowd – if the valuation is too high, the crowd won’t buy it – and there is some truth in this. However the crowd is easily swayed by a bunch of non-financial/fundamental arguments – e.g. the momentum of the fundraise, the quality of the brand/comms, etc.

There is a reason why Food/Drink businesses preponderate. People love them. They become emotionally attached. They aren’t paying attention to the numbers, they are investing in their local brewery. Or they love the packaging. Or they rave about the funky taste of this cool eco weenie woke juice. If Woke Brewillery is asking to be valued, as a loss making business with not much growth, at >10x annual Revenues, it might not matter if enough Woke customers decide they’d like to own £500 of shares. As the crowd builds, others say ‘ooh look, this is hot – these wealthy crowd investors must be onto something’. And then as the investing deadline nears, FOMO does the rest.

You might be wondering why, given how company-biased the crowd platforms are, more strong companies don’t use them. In my experience, the best companies start with ‘branded venture capital firms’ – who will pay exalted valuations for the best businesses, but turn down 95% of what they see. The rejected companies then try the 2nd tier VC firms. Only after they have been rejected from them too do they turn to the crowd – where they ask for similarly exalted valuations and nobody has the incentive or power to push back.

Why returns suck 2: Exits are very rare.

The other obvious explanation of why returns suck is simply how rare exits are.

I don’t have any comparative data here, but I can tell you that based on my survey data it is pretty astonishing that 80% of my audience’s crowdinvestors have never seen an exit.

And I reflect on how professional venture capital firms will usually have a seat on the board, or at least direct access to the management team, and will at some point start agitating for some form of exit – even if it is at a loss.

I reflect on how the best angel investments often go on to raise venture capital investment, getting them into a ‘professional money’ asset class. And often on this journey there are opportunities for earlier investors to sell some or even all of their stake.

Crowdfunded companies don’t give the crowd any seat at the table. They do often give them some shareholder updates, but in a very broadcast sense, not in a dialogue sense. These companies usually do NOT go on to raise professional money – often due to the crippling high valuations of their earlier crowdfunding round, which puts professionals off and leaves the company facing an embarrassing ‘down round’ if they raise later money at a lower valuation.

Finding the exceptions that prove the rule

Surely, I sense some readers asking, there are exceptions? Surely there are some diamonds in the crowded rough?

Indeed there might be, I accept. I don’t have much experience to share with you but I can tell you what I’d look for:

- I’d favour platforms that attempt to solve the ‘company:crowd asymmetry’ problem. I have always liked the idea behind the Syndicate Room and Angel List in that they require an experienced angel to agree the terms and have their own skin in the game – and then the platform offers the crowd access on the same terms. These guys haven’t built the scale of the market leaders, because companies clearly prefer platforms where they have more power. I have no idea what returns they’ve achieved. But their process should be better.

- I’d look for strong reasons for the company to use the crowd other than raising money. For some companies, there are good reasons to encourage the crowd to invest, even when no money is required. Crowd investors become passionate advocates of their companies, often boosting marketing and growth. Boosting growth / loyalty is the most obvious ‘strong reason’. I can see, for instance, why some fintech firms go to the crowd, especially when they then incentivise investors to be customers and vice versa. I don’t know the specifics but I believe that Monzo and others have sought crowd involvement for ‘strong reasons’.

- I’d favour investments where the crowd is co-investing with professionals, on equal terms. There are occasions where the firm raises money from experienced VCs but then opens it up to the crowd to top up. If the crowd is being offered equal treatment, i.e. the same shares at the same prices, then suddenly your odds have improved a lot. These investments are rare but I know of a couple so I assume more exist.

- I’d prefer investments where the top table includes good investors. Seeing investors / venture capital firms around the board table would be good, especially if any of these firms has a name/reputation you can cross reference. Seeing a separate Chair to the MD/CEO is also a good sign, as it suggests a slightly more professional arrangement than one mediocre/maverick MD who has already been rejected by the smart money and is pinning his hopes on one last, desperate throw of his dice into the crowd.

I’d welcome comments, particularly those from investors with experience of the crowd – please give an indication of your experience if you can.

As you mention, private investments need to be looked in tandem with holding period. A portfolio of 0 exits with a holding period of < 5 years doesn't offer much insight.

A better way to gauge success, and this requires some analysis, would have been to ask are your private investments performing below, as expected, or above forecasts/expectations.

Variable pricing on the secondary market on Seedrs is a bit of a game changer. That could be a better proxy for the status of your investment without having to do much work.

But looking at exit as the be-and-end all doesn't paint the full picture.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] V London – Crowdfunding: why its returns suck An insightful look at crowdlending. I’ve never invested in any crowdfunding, although have […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

The simple fact for me is this:

If they were worth investing in, they probably wouldn’t be crowdfunding – they would have already picked up an angel investor.

Almost by definition, then, crowdfunded companies are those that nobody else wanted. Sure, occasionally you may find the unicorn that the professionals missed… but that’s like picking the 100/1 outsider at the races: you’re still going to lose a lot more than you win

LikeLike

I agree but disagree.

I agree that most crowdfunding businesses can’t raise money from ‘better’ sources. They are indeed companies that ‘smarter’ people didn’t want.

However investments of more than £100k from one angel investor are rare, in my experience. Whereas most crowd rounds will be a multiple of that.

LikeLike

It all comes down to research IMHO. If you aren’t doing your homework then it very much becomes a case of choosing a bunch of companies and praying at least one is the next Revolut to cover your losses.

Avoiding the losers can be equally as important as picking the winners, and that isn’t actually too hard. Just be cynical, do some thorough DD (why are they using the crowd is one such question, there can legitimate reasons). Don’t be fooled by the flashy investor packs, unrealistic forecasts. Question everything. If something doesn’t feel right, run. You need an extremely high hurdle. You’ll miss some winners, that comes with the territory.

In my view, 95% of pitches are junk, 4% interesting, 1% investable. Occasionally you come across the “no brainier”. But when they do come along, and you have done the work and built conviction, it can warrant taking an outsized position given the EIS skew. I still scratch my head when I see the 30% HMRC dividend, free HMRC put (tax-loss relief), and capital-gains free upside. It’s generous because most people lose, it’s a tax arbitrage if you know how to win.

Less and more concentrated bets is a superior strategy in my view. Crowdfunding requires a thorough, bottom-up approach. A top-down, spreading your bets and hoping for a 100 bagger is a flawed approach when 95% is junk.

LikeLike

I’ve invested in about 30 crowd fund companies – I’ve had one exit of 15x and another two of 2x so far along with 7-8 failures, so on a net basis so far so good I’d say, taking all the tax benefits into account.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree with John above, the overall holding period is a very important factor to consider. As the vast majority of the respondents probably invested in the last 5 years, exits should only start picking up now. Also the secondary market on Seedrs is much more liquid than before with £1 million monthly volume reached a few months ago, so you don’t necessarily need an exit to profit.

I’ve also found this article about one of these large exits you asked for. Apparently a business exited last month delivering a 120x return to its earliest investors in 2015 (332x return including SEIS). https://www.crowdfundinsider.com/2021/01/171238-crowdfunded-on-seedrs-investors-in-senta-to-receive-up-to-120x-return-as-company-is-acquired/amp/

LikeLiked by 2 people

I totally understand where you’re coming from. But the fact is most private investors aren’t choosing between doing angel rounds or being able to get into Sequoia or Kleiner Perkins or crowdfunding. They are choosing between crowdfunding or perhaps VCT trusts (expensive, no chance of multibaggers) or the odd investment trust (some reasonable but subject to crazy drawdowns in bad times and discounts to NAV, and no tax breaks).

Not to mention the fact that those alternatives give you none of the benefits of crowdfunding, IMHO, which is networking, meeting other investors, talking to entrepreneurs, and so on. Again, for the average non-City banker / non-fund manager this is really unusual stuff. I think it’s valuable.

Will it be lucrative? Well, probably not, though the tax breaks do a lot of heavy lifting. The average person is very unlikely to be any better at picking unlisted companies than listed. But I still think a small allocation might be worthwhile for those who think they’ll enjoy the benefits/learnings I mentioned above (and the perks — they’re fun!)

I absolutely think some companies choose crowdfunding for marketing benefits. Personally I’ve skewed towards companies where I think having consumer advocates is beneficial.

In terms of returns, as you and others have noted, it’s still early days. Personally I made my first crowdfunded investment in crowdfunded mini-bonds in 2015. The portfolio grow, flowered, paid out some free beers on the way, and returned about 8% a year by the time it was retired. That’s accounting for one company that went bust. Mini-bonds turned out to be a gateway drug into crowdfunded equity for me, which is silly really as the equity at least gives you the chance of commensurate rewards.

Anyway, on the equity side I’ve done about 45-50 investments of wildly various sizes. This is the kind of volume a ‘serious’ crowdfunder needs to be doing IMHO. Either a lot, or one or two passion investments. If you do 5-10 the maths is well against you, as much as it would be with the superior pickings a VC fund enjoys.

I believe I was doing okay until the pandemic. I mark to the last fundraising (I know, Woodford etc!) or some other pricing event. But then I discount the whole lot by 50%. Going into 2020 this methodology had me ahead of cost, after tax breaks, on the ongoing portfolio. Now it has me very slightly behind after a few down rounds and blow ups.

I went in knowing “lemons ripen first” but it’s still painful to see the failures mount — six so far.

In terms of exits, I’ve had a couple so far, for low multiples in the 2x range. There are companies in my mini-VC portfolio I am still confident of making multi-bagging returns on (10x+ in at least two cases) but I’ve seriously dialed back my expectations for a couple of others due to the impact of Covid and, at least, more future dilution.

I now imagine after ten years this whole venture is probably going to deliver a positive return, but less than a global tracker… unless something really stellar happens. There’s still time, as I’m still plugging away — I aimed for 100 investments when I began, so only roughly halfway there. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Off topic, sorry: did you ever repay your margin loan or did you decide to persevere with it?

LikeLike

If you check out my target allocation https://firevlondon.com/my-investment-policy-statement/ you’ll see that I still have negative cash at about 12% of my total net portfolio value. This is a lot lower than it peaked at. The graph of leverage over time is on my monthly returns page, and is updated in real time https://firevlondon.com/monthly-returns/.

LikeLike

[…] Crowdfunding: why its returns suck – FireVLondon […]

LikeLike

[…] crowdfunding is indeed – for good or ill – very […]

LikeLike

[…] crowdfunding is indeed – for good or ill – very […]

LikeLike

[…] Despite the fluffy promotion about missions to change the world and all the rest of it, adverse selection looms large. […]

LikeLike

[…] Despite the fluffy promotion about missions to change the world and all the rest of it, adverse selection looms large. […]

LikeLike

[…] Pilihan yang buruk, terlepas dari kebingungan tentang misi yang mengubah dunia dan yang lainnya Itu terlihat sangat bagus. […]

LikeLike

[…] Despite the fluffy promotion about missions to change the world and all the rest of it, adverse selection looms large. […]

LikeLike

[…] Despite the fluffy promotion about missions to change the world and all the rest of it, adverse selection looms large. […]

LikeLike

[…] Despite the fluffy promotion about missions to change the world and all the rest of it, adverse selection looms large. […]

LikeLike

[…] Despite the fluffy promotion about missions to change the world and all the rest of it, adverse selection looms large. […]

LikeLike

[…] Despite the fluffy promotion about missions to change the world and all the rest of it, adverse selection looms large. […]

LikeLike

[…] Regardless of the fluffy promotion about missions to alter the world and all the remainder of it, adversarial choice looms giant. […]

LikeLike

[…] Despite the fluffy promotion about missions to change the world and all the rest of it, adverse selection looms large. […]

LikeLike

[…] Despite the fluffy promotion about missions to change the world and all the rest of it, adverse selection looms large. […]

LikeLike