It was just over two years ago that I first decided to use a margin loan to buy a multimillion pound Dream Home. It seems I’m one of very few folks, worldwide, to explicitly make this decision. So how’s it turned out? This post describes my journey so far. If you have no interest in margin loans or debt then this post isn’t for you – be warned.

What was I thinking?

The full story of that house purchasing whim is told in various posts (starting here), but it’s worth recapping a moment on my logic for using a margin loan.

The decision to buy the Dream Home arose very suddenly. I am not joking when I say it was a whim. All I knew for sure when I committed to the transaction was that I had liquid assets of a value significantly in excess of the Dream Home™, and that a mortgage wouldn’t be of much use to me. So I assumed that I could, worst case, sell assets to raise the funds necessary.

I needed to raise about 110% of the value of the Dream Home, to cover the purchase price, the stamp duty, and transaction costs.

My plan was to sell my Previous House shortly after buying the Dream Home (but not in a chain transaction). I assumed the Previous House was worth about 60% of the Dream Home. I also assumed the Previous House would be difficult to sell until after the Brexit referendum was behind us, at which point we would be safely confirmed as remaining in the EU. Hah. But even in my fantasy scenario, there were going to be many months between the purchase of the Dream Home and any sale of the Previous House, so I needed to ignore the Previous House when finding funds to complete the Dream Home transaction.

At around the same time, I was also expecting a windfall sum from the partial sale of one of my illiquid investments. This sum was going to be more than enough to pay for the stamp duty, i.e. a very significant windfall, of over 10% the value of the Dream Home. But I didn’t have control over the transaction timing and I knew that the deal could be delayed by weeks/months or, worse still, derail completely.

So, in crude terms, I thought that I could, over a few months and with a bit of risk, find about 70% of the ~110% I needed without needing to touch my portfolio, and that the balance of about 40% would come from liquidating a suitable slug of my portfolio. But in the meantime I would need to find potentially all 110% by liquidating the portfolio; this was going to be painful, but, hey, wasn’t the whole point of my liquidity-seeking investment strategy to be able to use the portfolio tactically when unexpected situations arose?

What should I have been thinking?

Once I thought about the funding requirement in more detail, in December 2015, a couple of things became clear.

First of all, my assets that were truly liquid were really my unsheltered portfolio assets, and if I sold enough to fund the Dream Home™ fully I wouldn’t have very much left in these.

Secondly, at exactly the moment that I became besotted with the Dream Home™, the UK equity markets took a marked turn for the worse. Two years of hindsight shows that this period was a relative blip in an otherwise smooth upward journey, but two years ago I obviously wasn’t sure what was going to happen. And I was cross that the value of my assets had dropped by a few hundred thousand pounds literally the week or so before I decided I wanted to liquidate those assets.

FTSE-100 index, 2013-2017

Now, I know the textbooks will tell you not to try to time markets. So I knew that my opinion on whether the drop in FTSE to 5900 was the start of worse to come, and I should expect a further drop to below 5000, or in fact I was in a temporary dip before FTSE would go on to soar above 8000, was not an opinion I should trust. But I remember feeling, and my blog posts from that era are living witness here, that I was confident FTSE was headed higher not lower in the medium/longer term. This made me profoundly reluctant to be selling out of the market too much. And I was prepared to back my judgement on this matter with my own cash.

All in all, the context here all pointed towards me having ‘a temporary difficulty with liquidity’ (to the tune of, ahem, £2m+) rather than towards a long term need to borrow money. This was, I felt, exactly what a good loan is designed for.

In terms of types of loan, I had three options to choose between:

- A mortgage. I was planning to buy the Dream Home™ debt-free. But I could instead have looked for a mortgage. However I didn’t like the sound of this; I wasn’t in London to organise it, I didn’t have the income to command much of a loan, and mortgages of £1m+ are notoriously hard to get.

- A loan from my private bank. I wasn’t too sure of the specifics but I was reasonably confident (and this is a testament to them and all those fees I’ve been paying them over the years) that my private bank would probably ‘lend a hand’ on a temporary period at least, in some flexible way, if I asked them to. But it would cost me.

- A margin loan. I had a little bit of experience with margin loans already at Interactive Brokers, just by experimenting with a High Yield Portfolio. Perhaps I could scale this approach up?

I had a quick conversation with my private banker about the situation and he almost immediately recommended I consider a margin loan. Given that this had been on my mind already I then looked into it seriously. And sure enough it looked compelling:

- The loan was to be secured on my existing portfolio. So no need to sell that portfolio.

- The rates were very low. Lower than a mortgage. Almost certainly lower than a funky private banking loan.

- There is a lot of flexibility. There is no repayment schedule, but you can repay as much as fast as you want with no penalties. You can swap currencies. You can pay down and then draw down again if you want to.

- No paperwork was required (for Interactive Brokers, at least; my private bank required a fairly simple letter to be signed). No arrangement fees. Easy.

- The only slight complication was that it proved only to be possible with two of my accounts – my private bank and Interactive Brokers. Not even my Goldman Sachs account, which I would have been perfect for margin-ing, would let me do this. So to make most use of it I would need to shuffle funds around considerably to move funds into the private bank and/or Interactive Brokers

What’s the catch?

What, I asked myself, is the catch from a margin loan? Aside from the obvious perils of debt – more on this shortly – there appeared to be only one clear catch: the loss of control.

With a mortgage you are committing to a particular repayment schedule, and provided you meet this schedule there is nothing the bank can do to you. You do not have to repay them in the way (i.e. from the sources, e.g. rental income, salary, bonus, etc) that you said you were going to – you simply need to get them their money on the dates you said you would. To me this has one chief advantage – you remain in control and your ultimate risk depends on your ability to pull rabbits out of hats.

With a margin loan, you are ceding to the broker the ability to liquidate your portfolio in any manner it sees fit, without notice, based on circumstances that you can’t control and can’t necessarily see coming. This is nerve-wracking to put it mildly. I don’t like selling assets at any time, and selling assets when prices have plunged is worse still (however much this feeling may be simply an erroneous cognitive bias). But having somebody else do that for you against your wishes sounds truly awful.

The broker will give you a clear formula for determining when it will start recovering its money – initially by giving you warnings and then subsequently by forced liquidations. The formula sounds simple enough: if the loan climbs above a certain % of your portfolio value, you get a warning; if it climbs above an even higher % then liquidations occur. But in practice I find the formula confusing and not intuitive – it is a bit like a yield, in that things behave ‘upside down’. I can explain it to my smart mates in the pub easily enough. But I knew back in 2015 from my HYP experience, and I continue to think two years later, that the reporting, the metrics, the formulae, the language all require careful attention. For me, the margin process was and remains something to be wary of. Handling margin loans in adversity is not for the faint-hearted.

In fact one thing I discovered literally at the eleventh hour of drawing down the margin loan is that there is a further risk that I hadn’t spotted. A very serious risk. This is that your broker can, and sometimes does, dramatically move the goalposts (with no notice) in terms of how ‘marginable’ a security is. This happened to me where one of biggest holdings suddenly (based on low trading volumes) dropped from ‘normal’ to ‘unmarginable’ overnight; in effect this suddenly excluded one of my biggest holdings from my collateral. It continues to happen to me with some surprising holdings; for instance, Interactive Brokers will not give margin on the Vanguard Australian ETFs, and the only easy way to discover this is by trial and error – i.e. you buy the ETFs first and then see that your available funds are much lower than you expected.

If, for instance, Vanguard or iShares en bloc became unmarginable, then despite having a portfolio far in excess of what is theoretically required as collateral, I might face margin calls in a downturn. I can’t imagine why or how Vanguard or iShares securities could all become unmarginable but I know enough to know that just because I can’t imagine it doesn’t mean it can’t happen. Taleb, eat your heart out.

There was one additional difference I had in mind. If your margin loan costs less than 2%, and you use it only to buy assets which yield 3% or more, and these assets are in the same account as the loan and thus naturally service the interest payments, then ‘auto pilot’ will look after you. This is quite unlike a mortgage on a primary residence, where the house being purchased (as taught to me by Rich Dad, Poor Dad) is a drain on your cash (i.e. a liability), not a provider of cash (i.e. an asset, as my parents would have taught me), and so the need to make mortgage payments just makes it all worse.

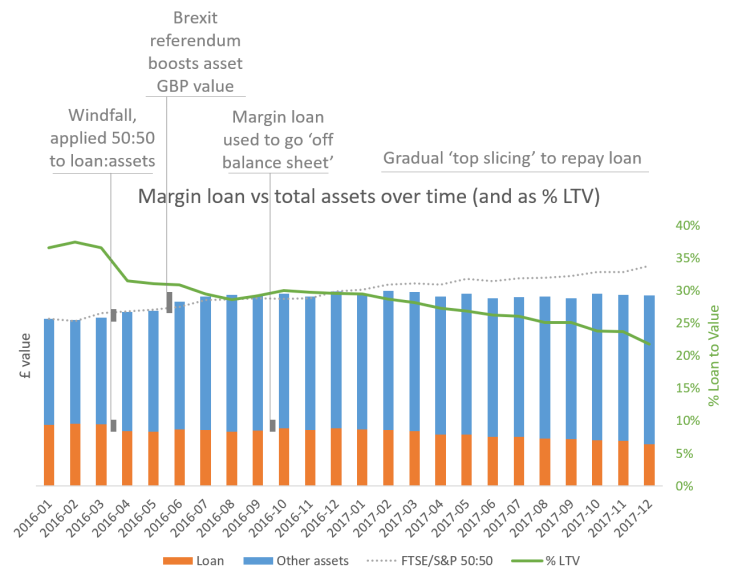

Anyway, as readers will know, I ended up taking out a significant amount of margin loan. I split it across both providers, and reorganised quite a bit of my portfolio to suit. Just after paying the stamp duty in February 2016, my loan peaked at over £2m, and about 37% of my portfolio’s assets’ value.

What’s the worst that can happen?

I considered a margin of 37% of my portfolio value to be considerably higher than I was comfortable with. Why? What was an appropriate long term loan level?

In simple terms, my portfolio loans weren’t allowed to be more than 50% of the margin-ed portfolio. My private bank will advance a loan of up to 70% for most assets but IB generally runs at 50% and I regard 50% as the practical ceiling.

My thinking that I needed to be able to withstand a sudden market crash. Ideally, I wanted to be able to withstand it just with the funds in the margined accounts, but this was quite a high bar. In a tough crash, I was prepared to have to liquidate assets in other accounts (e.g. Fidelity) in order to avoid margin calls in e.g. Interactive Brokers.

How much of a crash? My rule of thumb was to be able to survive a crash which hit my assets by 30%. Equities can certainly fall by more than that – and quite frequently do – but blended portfolios are less volatile. For context, a USA 60/40 portfolio drew down 27% in the 2007-2009 crisis (https://seekingalpha.com/article/4080602-60-40-portfolio-risky-investment). I tilted my portfolio slightly more to bonds in order to get it closer to a 60/40 mix than I would normally run it at.

With a loan to value of 37%, a 30% drop in total asset value would have seen the loan become 54% of the total value. This was too high. To ensure the loan couldn’t exceed 50% of the portfolio, even after the market crashed by 30%, the loan must start off at less than 35% of the total portfolio. So I was kicking off with a loan that was £100k+ too big, and I knew it.

Moreover, although against a ceiling of 50% a LTV of 37% doesn’t sound too bad, in practice it was much tighter. My total portfolio value included assets in other accounts, much of which sheltered from tax in in ISAs/etc, which weren’t margin-able and withdrawing funds was either hard or (as in a SIPP) impossible. So the LTV in the accounts which contained the margin was actually practically 50%. This left me with very little room for further market falls before i would have needed to top up the margin-ed accounts from other accounts And the unsheltered accounts that I could have easily topped up from didn’t have much in them, and what they had would presumably have dropped in value in this scenario too.

I was carrying significant risk here, much of which I knew but arguably some of which I didn’t.

What happened next?

As I mentioned above, I was expecting two significant inflows of cash within a few months of taking out the margin loan: the sale of the angel investment, and the sale of the Previous House.

As things turned out, the illiquid investment sale came through in April, and I used half of this windfall to reduce the loan and half of it to buy additional margin-able assets, both activities helping to reduce my Loan To Value ratio. But the Previous House didn’t sell and I ended up letting it out.

The good news here was that, thanks to the windfall, by April I had repaid enough of the margin loan to bring my LTV down to 32%. This left me out of my ‘30% crash’ danger zone but still more exposed than I felt comfortable with. This left me facing a potential drop in my portfolio value of over 40% if the market fell 30%, and would have left me raiding my tax-sheltered assets to meet margin calls, probably unable to rely on investment income and forced to get paid work, or having to cut my standard of living – none of which was very appealing.

For the next few months my strategy was to redeploy all my investment income in margin-ed accounts into reducing my margin loan. In theory this would mean paying off the loans by over 2% a year, which hopefully would occur against a backdrop of rising capital values too.

Fortunately for me, Q2 2016 saw the UK markets recover slightly – the FTSE-100 stabilised at over 6000. The S&P500, having dropped in Q1 below 1900, finished Q1 at almost 2100 and thereafter began a rise which has continued almost to this day. The rising markets pulled me further out of the risky woods.

Heh, this debt is *fun* isn’t it

So, in the summer of 2016 with markets rising, in theory my LTV should have been dropping significantly, as I repaid the loan slowly out of income and the value of the portfolio rose with the markets.

In practice I ended Q2 with my loan having expanded by £70k. What happened? I found myself regularly nibbling at the market, buying into positions and generally marvelling at my seemingly limitless funds.

Doing my quarterly blog updates shone a light on the gap between my strategy and my practice. I realised that before my margin loan, I was used to spending what I had; so as cash appeared in the account from dividends etc, I would spend that. With the margin loan, there is no natural buffer – once your cash balance says -£1,034,421 but you can still spend £11k on a stock you have taken a shine to, your new balance of -£1,045,678 doesn’t really feel any different. And your net portfolio value hasn’t changed, but your income yield has probably just risen. So overall it all feels very comfortable. But, oops, your LTV has just risen in a rising market, which wasn’t what I’d promised myself.

This highlighted an important aspect of margin loans for me. Once set up, they are incredibly easy and flexible. Arguably too much so. No permission is needed, with IB at least, to simply keep extending the loan – provided you are nowhere near your debt limits. You don’t really see the interest payments either, as they are not very visible in the monthly reporting at all. Overall I love margin loans for this, but it means you do need to find a way of maintaining discipline – and ‘spending as much as I can’ is no longer very advisable!

Referendum and margin risk

I had made the call early in 2016 to reduce my exposure to the UK. This was because, though I thought Remain would win the Brexit referendum, I saw a lot more downside risk if they lost than upside gain if they won. As a result I had reduced my exposure to the UK dramatically. With hindsight, what I should also have done is put all my borrowing in GBP; what I had actually done was split my borrowing between GBP and USD.

In any case, as we all know, Leave won the referendum 52:48. And the pound suffered its biggest drop in over 30 years. And the overseas-dominated FTSE-100 actually quickly rose above 6500. Alongside this, the Bank of England lowered the sterling interest rates from close to zero to, well, even closer to zero. This was all great news for my margin loan. The only fly in the ointment was that my USD debt was now larger in GBP terms, but so were my USD assets.

Thanks to the referendum, my portfolio gained 10% in value from May to July. During this period I made some opportunistic purchases (including Persimmon @ £13, yay!), and my margin loan rose by £80k. Hooray for the margin loan and its wonderful flexibility – although I would have a very different view if the market had carried on plummeting in July. Yet even with me expanding the loan opportunistically, my LTV dropped by over 1%.

By August I was on a mission to pay down some of the loan so I sold some assets to do so, and by the end of August the loan was no bigger than it had been at the end of May, but with the portfolio almost 15% more valuable my LTV had dropped below 29%. In effect I had used the loan facility as cash, taking advantage of some buying opportunities in real time, and then figured out a few weeks later what to sell to fund the purchase.

Risk on/Risk off vs Market timing

In the last few months of 2016, with the markets continuing their relentless rise, I made a conscious decision to move some of my assets out of the liquid markets and into other opportunities. I lent some money (still waiting for the blog post…), I bought some shares in a friend’s company, and so on. To some extent, I was using my margin loan to fund this, but with my LTV at under 30% I was feeling phlegmatic about doing so. Somehow, an LTV of 30% felt quite conservative.

Having dropped below 29% in August, my LTV crept up (in a rising market) to 30% in October, before ending up at year end at about 29.5%.

I have long believed that it is pointless to try to time the markets. I believe all those analyses which suggest it is all about time in the market, not timing the market.

But as 2016 came to a close, and the chorus of ‘is the market overvalued? when will the bubble burst?’ became louder, I remembered the 2007-9 period and how there was a clear ‘Risk On/Risk Off’ behaviour in the market. With a 30% LTV I was clearly Risk On. And if the market turned, any losses would be amplified by 30%. This didn’t feel sensible to me. And my psychology started to change.

How I have been thinking about market timing, leverage and risk during 2017 is significantly different to how I thought about it in 2016. I now think that it is one thing not timing the markets, but if by selling out of equities I am simply reducing my leverage, then I’m far from sure this counts as ‘getting out of the market’. I’m still very much in the market. So for much of 2017 I have been deliberately reducing my positions.

My way of trying to discipline myself and resist the short term urges is to set my target allocation and regularly review my progress against it. So for me the way to implement ‘Risk Off’ is to adjust my target allocation into a less leveraged posture. This way, if I see opportunistic buy opportunities, I can still take them – even if that moves away from my target allocation – but when the gust of wind passes I will naturally find myself tending to the garden in the direction of my target allocation.

I made a small downward adjustment in target leverage in July 2016. I made another one in January 2017, and I made another quite big one in October 2017.

2017, and the first rate rises in a decade

I went into 2017 believing that Trump was probably, if anything, going to be good for US equities, and seeing no reason to shift my investment strategy very much. I also thought that if markets continued to rise I should take the opportunity to reduce my leverage, because when the fall eventually happened I didn’t fancy having it amplified by a lot of leverage.

So as 2017 progressed, and markets continued to reach new highs – particularly in the USA, I found myself becoming increasingly determined to ‘top slice’, i.e. take profits, and reduce the absolute size of my loan. This was most pronounced in Q4. By doing this, my total assets have not grown in line with the wider market – a crude approximation of which (50:50 blend of FTSE and S&P500) is shown as a dotted line in the chart below – but my net assets (the blue portion of the total asset columns) has in fact outperformed the market.

The month-by-month progression of my loan (L), total assets (V) and LTV (L/V) is shown below.

In fact 2017 has seen the first rises in base rates for a decade, beginning in the USA. At the time of writing I now pay about 2.5% for my USD loan, and about 1.75% for my GBP loan. I’ve reacted to these rises by shifting much of my loan from USD to GBP.

There is a wider point about margin loans and rates. Bearing in mind the tax wedge on dividend income, in the USA margin loans are no longer covered by average dividends, and in the UK one further rise of 25bps would be enough to tip margin from ‘profitable’ into ‘not profitable’, at normal yields (‘profitable’ meaning after income taxes on dividends/interest).

I finished 2017 with my total LTV down to 22% (from 37%). And even the LTV against just the accounts with margin is a much healthier 28% (from 51%). I’ve got my safety buffer back.

What impact have I seen on my returns?

Given that my average leverage over the last two years has been about 30%, and that markets have risen significantly in this time, have I outperformed the markets by 30%?

I’ll do a separate post on my performance over the last few years but the short answer is, No, I have not outperformed by as much as my leverage would suggest. I don’t know why not – is it because my investments choices are underperforming? Quite possibly. Is it because of the costs of finance? No, not entirely. Is it due to money-weighted effects (i.e. my portfolio has increased/decreased in size at funny times)? Possibly, but only partially.

The future: what is the right level of leverage?

By the end of 2017 I have managed to reduce my leverage down very close to my target level. This target, in which the loan accounts for 25% of my net portfolio value, and 20% LTV of the gross value, is an arbitrary level. What is the ‘right’ level?

For me there are four factors I consider to arrive at the ‘right’ level for me:

- Exposure to a large drawdown. At a 20% LTV, a drop of 30% of the gross value would see a 37% drop in my net portfolio. How would I feel about a 37% drop in net value? In theory, I could cope with this – it would put me down a level not much lower than I was immediately after buying the Dream Home at the start of 2016. And, in theory, I knew at that point the market could have fallen further in 2016, so if I was OK with it then I ought to be OK with it now. In practice, and revealing the loss aversion we all exhibit, I would find a 37% drop in my net portfolio value pretty hard to stomach. I think I could do it, but I also know I’d be miserable for months.

- Funding costs. Once the interest cost exceeds 2%, it isn’t covered by dividends after taxes. I tend to think of my long term average return as about 7%, pre tax, so I can make a case for sustaining leverage even at interest costs of around 3%. But certainly with rates above 3% I don’t think leverage adds much value.

- Quantum of debt. All the arguments I’ve laid out above are all based on percentages. But to some extent the absolute quantum matters too. At its maximum, my margin loan was around £2m. I was also carrying mortgage debt of over £1m, on other properties. Having over £3m of total debt, while very rational based on the assets and the costs of debt, makes Mrs FvL nervous. As at today my total is closer to £2m than £3m, and I can see a path to my margin loan being under £1m. At that level it is about five years’ worth of investment income. That feels very manageable.

- Market cycle. I remember the tail end of the 2008/2009 crash. I was trying to buy stocks. I rapidly ran out of cash. I remember every new dividend / coupon payment coming in was a moment of excitement because it gave me a bit more ammunition to go out into the market with. This would have been the perfect time to be extending my margin loan to buy stocks. Hindsight is a wonderful thing, and market timing is not, but I still consider that the ‘right’ level of leverage must fluctuate through the market cycle. Whatever my maximum level is, now isn’t the time to be there.

So, weighing these factors together, I think my ‘optimum’ level of leverage is an LTV of between 5% and 20%. And right now, with funding costs still low but the market showing many ‘top of cycle’ signs, it feels like I should be in the 10-15% range. So I still have some way to go.

Fascinating. Have a very similar situation i.e. liquidity concerns over next house purchase. Great to fill in some of the detail..

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, thanks FvL for sharing so much of your thought process and the mechanics of your financing. A very enjoyable read.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Quite a detailed analysis, thanks … but … margin lending rates of 2.5% and 1.75%?

I’d hate to do the same thing as you with margin lending rates at the level they are in Australia at the moment, a minimum variable rate of 5.2%, which is relatively low in historical terms.

This is a typical example from an Australian retail broker:

https://www.nabtrade.com.au/features/products/margin-lending

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, at higher rates the whole rationale collapses especially if (as for a UK individual tax-payer) interest isn’t tax deductible. Right now USD rates are almost as high as AUD rates. But IB is much cheaper than NAB and does offer AUD – starting at 2.947% and dropping to 1.947% at scale. https://www.interactivebrokers.com/en/index.php?f=1595

LikeLiked by 1 person

and are these lending rates variable? i.e. can the broker change them at any time?

LikeLike

Yes they are. Rates and threshold completely variable.

LikeLike

[…] Borrowing £2m to buy equities: Two years later – FireVLondon […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

Are you contemplating having another go at selling your old house? Stock up on cash for the coming market crash!

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] my (slowly deleveraging) allocation. Really I have two intentions here. First of all I want to continue to deleverage, which means my target allocation will slowly change from minus 25% cash to, probably, minus 20% […]

LikeLike

Hi FvL,

Thanks for sharing this – it was yourself who raised my knowledge of margin loans and something I now have at the back of my mind. I am also relieved to know that I am not the only person who accidently buys a house in London 🙂

I am going to take a look at interactive brokers based on this, maybe I need to start building up some unsheltered investments with them for the future….

Thanks for sharing – really good to read

Cheers,

FiL

LikeLiked by 1 person

In the great depression, didn’t many private investors lose everything when they had purchased unit trusts on margin? It’s a dangerous game you are playing in my eyes and your dream home is also at risk. Even at 20% ltv, who is to say equities could never fall 80%? They could and with trump as captain capitalism, things could get really tasty. If you got a margin call at 20% you may find yourself teetering on the edge of a big building in canary wharf. Do you have kids? Be careful…many a man has played this game and lost everything.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good to hear voices of caution. But I don’t see the dangers quite as you do. I don’t think my Dream Home is directly at risk; it isn’t the collateral for any debt. My invested portfolio is not my whole net worth, so I have other assets (e.g. the Dream Home) which I could liquidate (albeit painfully and possibly slowly) if needed. Thirdly equities are only a portion of my portfolio so even if, heaven forbid, equities drop 80% that doesn’t mean my wider portfolio would. But yet my psychology would take a major hit if equities fell 80% and who knows how that would affect things.

LikeLike

[…] Interactive Brokers, it has the biggest single amount of my portfolio and I don’t need its margin loan facilities as much as I did. So I have taken the opportunity to bump up the allocation to some of […]

LikeLike

[…] I was pretty exposed. If the market had dropped 30% I would have been panicking. Fortunately, as hindsight shows, it turned out very differently; world equities are up almost 60% since then. Brexit has […]

LikeLike

[…] I am leveraged. […]

LikeLike

[…] leverage/loan position remains in very safe shape, compared to fairly recent history. My loan represents less than the targeted 12% of the gross value of my portfolio, even excluding […]

LikeLike

[…] high-flying types, such as the blogger Fire V London, have used margin debt to buy a property. What’s more, he’d favoured a margin loan despite having a private […]

LikeLike

IBKR has a margin preview tool in their Trader Workstation platform, whereby you can check the margin impact of a potential trade, so you do not have to trade first and then check the account window to see what your margin is sitting at.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] I no ready cash funds available, I dip into my publicly quoted portfolio to pay for it. Thanks to my margin loans, this doesn’t involve selling anything; I simply withdraw £10k/£20k/£30k from my margined […]

LikeLike

Looking into this to assist with topping up the funds required for a family members home move. I only have funds available in a Shares ISA and can see IBKR don’t offer ISAs . Would anyone have any other thoughts on if this would be possible elsewhere?

LikeLike

I understand you can not borrow money against ISAs, in the UK – under some rules somewhere I forget. Bad luck!

The other options in UK, beyond IBKR, are the private banks e.g. barclays, ubs, coutts etc. However they all cost somewhat more than IBKR. Barclays is about 2.5% at the moment, for instance.

LikeLike

OK that’s what I feared, thank you for the fast response to this old thread I dug out 🙂

LikeLike

[…] high-flying types, such as the blogger Fire V London, have used margin debt to buy a property. What’s more, he’d favoured a margin loan despite having a private bank […]

LikeLike

[…] high-flying types, such as the blogger Fire V London, have used margin debt to buy a property. What’s more, he’d favoured a margin loan despite having a private bank […]

LikeLike

[…] sums in other unmargined accounts (e.g. ISAs), so I felt able to manage the risk – and in time a combination of that windfall, and stockmarket gains pulled my leverage down well below 30% in a matter of […]

LikeLike

[…] high-flying types, such as the blogger Fire V London, have used margin debt to buy a property. What’s more, he’d favoured a margin loan despite having a private bank […]

LikeLike

Great postt thankyou

LikeLike